Exactly 50 years ago, Berkeley Unified integrated all its elementary schools, taking an unprecedented approach. In a special three-part series, Beyond the Buses, Berkeleyside explores that history, its legacy and the equity issues that remain unsolved. The first installment looked at the past and its implications in a changing Berkeley. Today we look at a new high-school program trying to achieve what others before it have not. Tomorrow we train the lens on teacher diversity.

The bleachers were jammed with hundreds of 14-year-olds waiting for their Berkeley High freshman orientation to begin.

Some had been lucky enough to link up with old friends before entering the school’s gym for the late-August morning event. Others stood next to strangers, scanning the room with curiosity and scoping out their new classmates.

John Villavicencio, the school’s student activities leader, took the microphone and led the new freshmen in a series of rousing activities all meant to communicate some version of “We’re all in this together,” “You have to work hard and take risks,” or “High school is going to be fun, we swear!” There was a game of Simon Says, a team basketball challenge where students kicked their shoes into the nets, a rap performance by the school counselors, and an uncoordinated attempt at the Electric Slide by older students who’d signed up to be the teens’ mentors.

Some of the freshmen tried to play it cool, rolling their eyes at the display, middle-school-style. But even some of the sullen ones shrieked when Buzz, the school’s yellowjacket mascot, ran out and joined the dance performance.

In previous years, this sense of camaraderie would dissipate soon after orientation, as freshmen embarked on their respective first-year journeys to different “small learning communities” inside the larger high school. Some would have studied in the arts-oriented small school, others would have landed in the International Baccalaureate program, and still others would have headed to one of the other distinct programs at the 3,100-person Berkeley High. In the past, one student’s experience at the institution could look nothing like her best friend’s.

But this fall marked the launch of the “universal ninth grade,” an overhaul of the old program, and the first time, at least in many years, that every single freshman at Berkeley High is taking the same four core classes.

The goal of the universal ninth grade, or U9, is to start each Berkeley High student off on an equal footing, and for teachers to really get to know them, in an attempt to unify students and eliminate academic disparities. U9 was designed by a group of teachers and administrators over two years, through a public process that brought out passionate proponents and critics. The project is ambitious, and expensive — half a million dollars for just 2018-19, in a year when the School Board made $2 million in painful cuts elsewhere.

While the U9 program is new, efforts to “redesign” Berkeley High in the name of equity are not. There has been a catalog of initiatives over the years, aimed at making the massive institution more navigable and reducing the achievement gap — sometimes called the equity or opportunity gap — that has persisted in the 50 years since the district integrated all its schools.

One student’s experience at the school could look nothing like her best friend’s.

The U9 program divides all students into 120-person “hives.” Each teenager takes English, ethnic studies/social living, math and physics with other students in their hive. The teachers of those courses not only exclusively teach ninth grade, but also only teach students who are in the same hive. So each hive is assigned four teachers who are “all in,” and who can collaborate with each other and share notes about students and lessons.

Each ninth-grader, regardless of hive or teacher, is taught the same curriculum, so teachers can collaborate across the grade and attempt to send kids into sophomore year with a common academic background. Students can still take advanced math and two electives, and there’s a new course called LEAP (Learn, Engage, Accelerate, Persist), for those who need additional support. At the end of the year, all students will enroll in “small learning communities” or academic programs, like they used to do before high school started.

The question — one that won’t be truly answered for months or even years — is whether U9 will work better than the many other well-intentioned programs have in the past.

Staggering achievement gaps in BUSD

These days, it’s as much a cliché to mention the “two Berkeley Highs,” and to disparage the way the school district rides on its reputation of diversity, as it is to talk about how diverse the school is.

Beginning in the 1990s, especially, research projects and media began to complicate the narrative that Berkeley High was one of the nation’s most diverse and progressive schools.

In 1994, the controversial PBS Frontline documentary “School Colors” showed a Berkeley High campus rife with racial tension, violence, social segregation and de-facto tracking that put only white and Asian students on the path to academic success.

“Anyone who still believes or hopes or dreams that America’s schools are models for a more racially and ethnically integrated society will find ‘School Colors’ dispiriting,” opined a New York Times reviewer.

Some, however, did not mind the increased attention on equity issues at the school. Two years later, some of them paired up with UC Berkeley researchers to launch the Diversity Project, which grew into an extensive four-year initiative analyzing racial disparities at the school. The coordinators studied, shadowed, surveyed and directly included teachers, students and parents, in an attempt to determine the causes of the gaps and social segregation, and figure out how those issues were connected. They wanted others to be as concerned about those realities as they were and hoped to inspire efforts to make changes.

This was before “achievement gap” was a household term, said Dana Moran, a Berkeley High teacher who joined the Diversity Project shortly after she was hired in the early 1990s.

“Everyone kept going, ‘Everyone knows this. So what?’”

Granted, this was a different time at Berkeley High. Students registered for classes through a free-for-all in the gym, where they’d sprint around to sign up for specific teachers they wanted, in a system that landed the already-savvy with the strongest educators. The school was going through a string of principals who only stayed a year or two, and fires kept getting started on campus. In “Unfinished Business,” a 2006 book about the Diversity Project, Moran wrote that she was given an official part-time job of “Racial Harmony Coordinator,” a title that sounds either offensive or satirical today.

The project eventually had some success in its stated goal of “making the familiar seem problematic,” through publicizing data and extensive, candid interviews with students, parents and teachers. The result was a detailed portrait of a school that gave different students vastly different opportunities. The work prompted a number of changes — the creation of a parent resource center, for example, which is still run by Irma Parker, who was involved in the Diversity Project — and highlighted other policies that contributed to equity issues, such as counselor caseloads and class placement processes. It called on adults to do what they could to address serious social segregation and perceived barriers among students of color to certain classes and clubs.

In “Unfinished Business,” though, the Diversity Project leaders lamented that they didn’t spark the kind of large-scale change they wanted to.

“It really took until 2002 for Berkeley High to even own the problem,” Moran told Berkeleyside. “Everyone kept going, ‘Everyone knows this. So what?’ We said, ‘These different rates of achievement are not OK, right? All these black kids are getting suspended — not OK, right?’”

Today, nobody denies that the achievement gap exists or that it’s a problem. But the recognition has not eliminated the disparities, in Berkeley or across the United States.

Test scores hardly tell the whole story, but the gaping disparities in Berkeley’s numbers certainly say something.

In 2016-17 only 19% of black eighth-graders performed at or above grade level on standardized math tests, according to data recently presented by the district. Forty-six percent of Latino students were at grade level, as were 80% of white students. That black-white gap has actually grown over the past few years.

With reading, the district has made much more progress, but gaps still remain. In 2017-18, 65% of black third-graders were deemed reading-proficient, per state tests, as were 80% of Latino students and 93% of white students. The figures represent significant improvement for students of color over the past few years. Research suggests third grade performance is a strong predictor of later academic success. This year BUSD is introducing a phonics-based curriculum, expecting to help more students who struggle with reading.

The math and reading figures were included in a recent update on the 2020 Vision, a collaboration between the city of Berkeley, BUSD, UC Berkeley, Berkeley City College and others. The project is premised on the idea that eliminating racial disparities is a “cradle to career” effort, requiring infant health services to coordinate with K-12 reading programs and community college scholarships. Many such programs have arisen since the 2020 Vision launched in 2008, seeing positive, though not nearly sufficient, results. Progress is tracked by looking not only at test scores, but kindergarten readiness and school attendance rates too.

BUSD also analyzes students using the Academic Support Index, developed by David Stevens of the district’s Research, Evaluation and Assessment department. A student’s ASI score represents how many “headwinds” a student faces coming into a school. Those headwinds, per BUSD’s index, are things that make school more challenging for a student, such as learning disabilities, homelessness, not speaking English, having a history of academic difficulty and so forth. Each headwind is given a weight of 1 or 2 based on correlation with GPA, and used to calculate a student’s ASI, a number between 0 (no headwinds) and 8 (the most headwinds).

The ASI scores are meant to provide more nuanced predictions of the support a student will need as they make their way through Berkeley schools, and help the district distribute resources appropriately. Stevens’ analysis has shown an ASI score to be a strong predictor of many academic outcomes, and other districts have adopted the algorithm too.

BUSD credits the ASI system with more directly targeting “interventions,” and not simply, and problematically, pulling black kids out for an extra support class because as a group they test more poorly on average. Those interventions have ended up boosting state exit exam scores for black and Latino students, according to the district.

The ASI was created in part to respond to assumptions about student populations in Berkeley High’s small schools, and allegations about some students getting extra help unfairly. Berkeley High’s average ASI, according to a 2018 presentation by Stevens, is 1.96. The International Baccalaureate program’s is 1.15 and the Academy of Medicine and Public Service’s is 2.85. The former has a reputation of being the whitest program on campus, and the latter of being for students of color.

One of the Diversity Project’s recommendations was to divide BHS into small schools-within-a-school, each with populations reflective of the school’s racial and socioeconomic demographics, to promote personalized instruction.

Some were abandoned or reconfigured right after they were started, but for several years BHS has had the same three “small learning communities,” and two larger academic programs.

The small schools are beloved by many who participate in them, and give kids special opportunities like internships and media production training. Small school teachers say they develop real relationships with students and reach kids who’d otherwise drop out or get lost. Research has suggested “looping” — having kids work with the same teachers for multiple years — has positive outcomes.

But the small schools have also been criticized for giving students no or few chances to take AP or other advanced courses. With higher percentages of students of color in the small schools, that looks extra bad.

Each of the small schools and programs has developed its own reputation — some for being for “slackers” and others for being elitist. Those reputations reached the middle schools, where students, before U9, would have to select the program they’d be associated with before they even started high school.

“When I was vice principal I would often be the one to go out and speak to the eighth-graders,” said Berkeley High Principal Erin Schweng, one of the U9 architects. “It was incredibly disheartening to walk in and hear a student say, ‘I’m gonna be in blank, because I’m blank.’”

If a student didn’t get into their program of choice (it was a lottery), they’d start high school feeling like “I didn’t get something,” Schweng said. The universal ninth grade is supposed to let them settle into Berkeley High, observe the small schools with their own eyes, and make an informed decision.

Everyone gets taught the same thing

When U9 was first proposed, it was heralded by many as a modern-day desegregation initiative — 50 years after Berkeley voluntarily integrated its schools — and an antidote to the divisions created by small schools. It was partially created to comply with instruction from WASC, an accreditation commission, to racially integrate the campus.

Hasmig Minassian, a U9 teacher and another architect of the program, said that’s not how she thinks of it.

Desegregation “certainly wasn’t a primary factor” in the decision to create U9, she said. It was “bringing all those kids together so they can get their feet on the ground and make [small school enrollment] decisions in a more thoughtful way.” And so all 10th grade teachers knew exactly what they were getting — ideally “consistent, academically rigorous education across the grade level” — instead of a cohort of kids coming in with wildly different first-year experiences.

Berkeley High was already headed in that direction, with standardized Common Core math, and movement toward having all freshmen take ethnic studies and physics, which used to be a voluntary senior-level science class. The U9 program made it all official.

“It was an opportunity for us to make our ninth-grade program have a common set of expectations, culture and climate,” said Schweng.

When assigning freshmen to hives, staff first equally distributed students in advanced math, then did the same with students in special education, Minassian said. Race, class or other factors weren’t part of the formula, so the makeup of one hive is different than that of the next.

The U9 developers looked to research on “redesigning high schools,” by Stanford’s Linda Darling-Hammond, for guidance.

In her report, Darling-Hammond, president of the Learning Policy Institute, said “personalization” was a fundamental feature of a successful and equitable high school. That must be achieved through smaller schools or structures, she and co-authors wrote, but size alone is not enough to ensure lasting relationships between teachers and students, and instruction tailored to each child’s needs.

During the first week in Minassian’s U9 ethnic studies class, she had her students express what worried them about ninth grade. They took turns scrawling their anxieties on the whiteboard. “Procrastination,” wrote more than one. “Balancing sports and homework.” “Being an annoying freshman.” “Overthinking about everything.” When one student scribbled a much more troubling response, Minassian read it aloud like all the others, without missing a beat.

But after class, she said the four-teacher team in her hive had already met to discuss multiple kids who were displaying warning signs. They reviewed the students’ files from middle school, and put their heads together to figure out how to provide coordinated support. That never would have happened in the past — at least not outside the small schools.

In each subject, U9 teachers are working with the same curriculum and have opportunities for professional development with their peers, or with all the U9 teachers. In the past, an educator might have taught both ninth- and 10-grade English, or a science class that not all freshman took, so they couldn’t share notes with others in their same situation. In small schools, there is sometimes only one teacher working with a given subject or curriculum.

For a small handful of the students, U9 will be complemented by another brand-new equity initiative, the African American Success Project. The program was created with funds set aside in the district’s budget last year to support black students struggling with academics. A group of 100 or so students will get case-management — one-on-one mentorship and phone calls home — and social opportunities. The curated group includes students who have “maxed out” on the resources available to them and are still struggling, or children who have not been “on our radar for whatever reason” until now, said Kamar O’Guinn, a former Oakland charter school administrator hired to craft and oversee the program.

O’Guinn said he heard a constant refrain during his initial visits to Berkeley schools. Students and staff often said they felt isolated.

“With the shrinking population of African American students in Berkeley, we want to make sure those students have an opportunity to build community, to make sure they feel like they belong,” O’Guinn said. “Coming from outside of Berkeley, when I look at what’s available, there are so many resources. But what I hear is it’s hard to navigate.”

Does a common program like U9 “gentrify” Berkeley High?

Most of the pushback against the U9 proposal came from parents who thought the plan neglected advanced students, and small-school advocates who feared the loss of a year of their highly structured programs.

The LEAP class, where students double down on their academic lessons and learn college and career skills, was voluntary, but was recommended to some students by middle school counselors. Staff tried to avoid creating a stigma around it by assigning it credit that counts toward UC admission requirements, said Minassian, and by making it fun. There was less initial interest than expected, said Schweng, but families have called wanting a spot since school began. There is no equivalent offering for advanced students, but they’re given the option of taking honors math or an advanced language course as an elective, like before.

Pitting U9 against small schools is missing the point, proponents say. The designers of the program adopted some hallmarks of Berkeley’s small schools: a school-within-a-school structure, a strong ethnic studies course.

Is it our Brown mandate to strive to integrate every space?

But some teachers worried that by denying kids immediate access to the specialized communities, some students would slip through the cracks it was before too late. They wouldn’t find a place they felt comfortable and supported at Berkeley High, or a community where they felt they belonged.

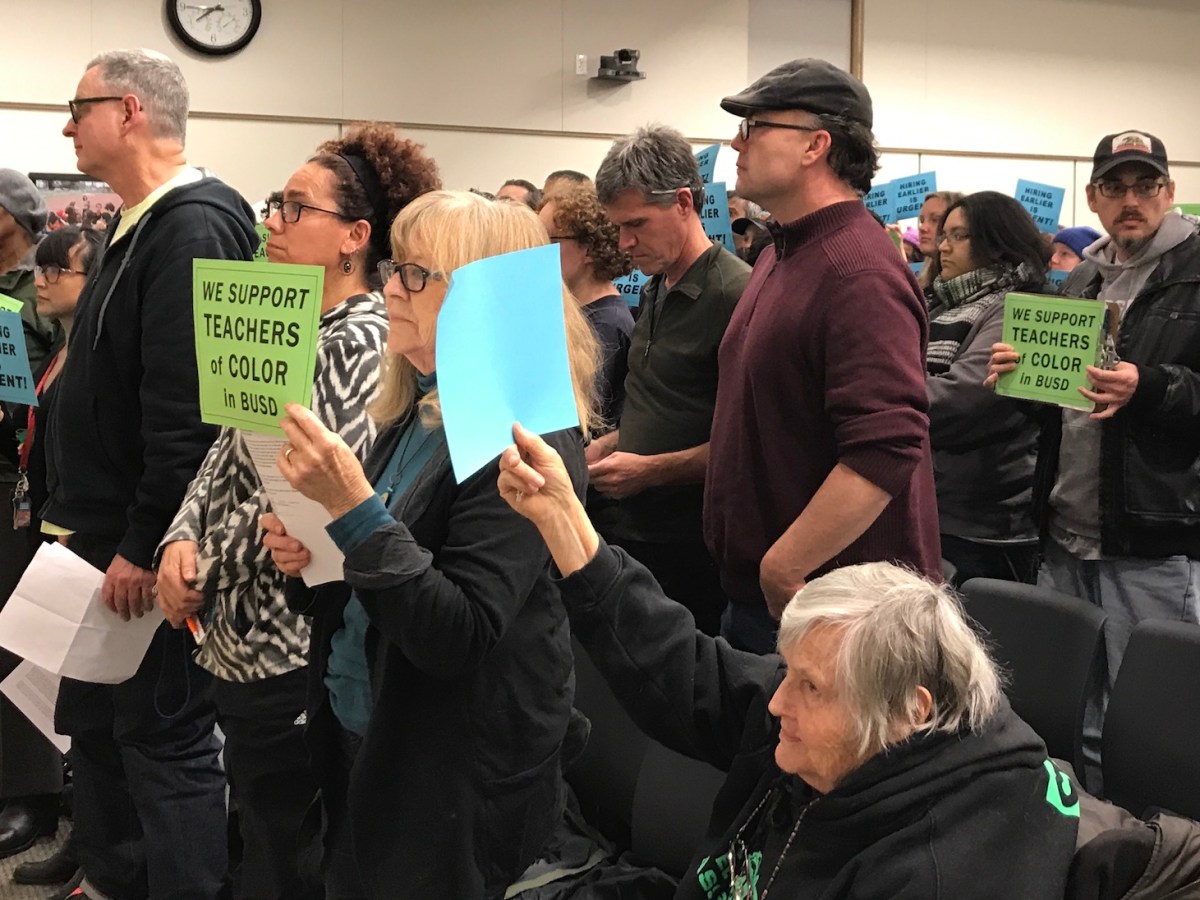

“My biggest fear is this autonomous space for black and brown students in [the Academy of Medicine and Public Service] will start to go away, and essentially you’ll be gentrifying my ninth grade,” said history teacher John Tobias at an emotional School Board meeting on U9 in 2017.

It’s an age-old debate in education. Should institutions that have historically neglected certain groups give those groups rooms of their own, to learn and express themselves without fear, to get and give each other support, to find an opportunity to get something wrong without feeling the pressure of representing an entire group? Or is it our Brown v. Board of Education mandate to strive to integrate every space, giving each student an equal opportunity to learn through equal resources and exposure to people with different backgrounds? Or something in the middle?

Minassian’s students mulled over such questions themselves in September, in a seminar-style class discussion where they were asked, “Should ethnic studies be a national graduation requirement?”

Almost everyone, of all backgrounds, said yes, all students should take ethnic studies, like they do in Berkeley. They said it could help “modernize” history, and help students learn their own stories or hear their peers’.

“Any downsides?” asked Minassian, perching on top of a student desk outside the discussion circle.

It would replace a regular history class, a student pointed out.

“White people might be embarrassed about all the bad things,” said one white boy.

“I disagree,” responded another. “You didn’t make those choices. Your ancestors did. If you learned about the history, you might want to change it.”

Many students said it boiled down to the teacher — who was leading the class, and how.

Student: “If we build up an ignorance of other races, we block them out.”

A black girl asked her classmates whether students should learn in a mixed setting, or just with people who share their experiences. She said she valued the diversity in her class, and the chance to “know about everyone’s background.”

“I’m all for sharing students’ life experiences, but race doesn’t matter at all,” said a white boy. “We’re all human.”

“I think understanding other races and cultures is a giant part of society,” responded another student. “If we build up an ignorance of other races, we block them out. The point of ethnic studies is to incorporate them.”

Those with strong long-term memories recall the Berkeley Experimental Schools Project of the 1970s, which divided BUSD into a whopping 23 alternative programs, with many like Black House and Casa de la Raza designed to be supportive spaces for racial minorities. Needless to say, with names like Genesis, Kilimanjaro and Yoga/Reading, those short-lived programs didn’t reflect today’s small schools.

Last year, then-senior Jahlil Rahim created what he felt was a critical refuge for him and his black, male peers at Berkeley High.

Rahim had come to Berkeley from schools in other states, and was frustrated to encounter what he felt was the same, if not worse, treatment of black students.

“Every week there was always a case of someone being sent to B-Tech or suspended,” he said. “I thought it was pretty crazy because a majority of kids I was in class with were white students, or non-black, and they would kind of let them off. But for the smallest offenses the black kids were suspended.” (B-Tech is the continuation high school. The district stopped involuntary transfers after a 2004 lawsuit alleging segregation.)

So Rahim started the Talented Tenth.

“I thought it would be best to form a group where young black men specifically could congregate among each other and give advice and have mentors that have the experience,” he said. The club’s name is a reference to a W.E.B. Du Bois essay on the need for African Americans to access education and become leaders in their communities.

“As a black man, you can’t afford to be like all these other kids out here.”

The young men met weekly and picked a topic to discuss. “One of main goals was self- evaluation. To serve your community you have to make sure you’re right in yourself,” Rahim said. Through connections to adult mentors, the students got access to everything from a workshop on tying a tie to a visit from now-retired Warriors player David West.

“This is a highly knowledgeable brother,” Rahim said. “When you hear him talk, you’ll forget he’s a basketball player. This dude goes into medic science, Ancient Africa…”

The Talented Tenth, which has continued since Rahim left BHS, also did community service work and went camping.

This fall, Rahim started his first year at Howard University, a historically black institution. He said the Berkeley High club was never about separating black students from the broader school or society, but about equipping them to navigate those settings.

“I’m the type to work in any environment,” he said. “You gotta be adaptable in this world.” When he got to Berkeley, he was surprised to by how quickly students would react strongly and vocally to all kinds of issues.

“They would go off at anything and everything,” he said. “That was another thing I sort of stressed at Talented Tenth: As a black man, you can’t afford to be like all these other kids out here.”

Principal: “Schools cannot solve the problem alone”

It won’t be easy for U9 leaders to redirect students — whether to new academic success, to bridge the achievement gap, or even to a different small school than they would have picked in the first place.

Research has repeatedly shown that a child’s earliest years are critical when it comes to determining their successes as an adult. Even by the time they enter kindergarten, some students have all those “headwinds” blowing against them. Integration plans can try to shuffle kids around the map, but they still go back home to segregated neighborhoods.

As for the so-called achievement gap, “schools cannot solve that problem alone, they just cannot,” Schweng said. “There are so many studies around prenatal care and inequities around preschool. Quite frankly, it’s institutionalized racism and white supremacy.”

Getting Down to The Facts II, the new second installment of a large California education research collaboration, stressed the need for more state support for early childhood education.

Schweng has worked in elementary, middle and high school settings in BUSD. At her current job, “it can be extra sad and extra discouraging to see a student who’s struggling, and probably has been in the same way, since third grade,” said Schweng.

By the time those freshmen entered the gym for their raucous orientation in August this year, many were already in precarious positions.

The U9 students read an Atlantic article called “Ninth Grade: The most important year in high school.” It taught them that more students fail freshman year than any other, and, when they do, the stigma and low self-esteem often make them drop out altogether. It’s a year when students are still developing rapidly, and meanwhile trying to make their way in a new, intimidating setting. Berkeley High held a “Ninth Grade Matters” forum aimed at imparting these messages, and providing support, to families of color.

In Minassian’s class, some students said they were skeptical reading the Atlantic piece. Don’t write some of us off from the outset, they said.

Schweng said it’s the high school students, who have opinions and are willing to express them — even or especially when it challenges the adults around them — that keep her from getting jaded or giving up the monumental task of changing lives. Some of the students were on the U9 planning team.

“Staying in public education,” said Schweng, “means asking, ‘What are the ways you can make a difference?’”