Exactly 50 years ago, Berkeley Unified integrated all its elementary schools, taking an unprecedented approach. In a special three-part series, Beyond the Buses, Berkeleyside explores that history. The first installment, published Tuesday, examined the district’s legacy and the equity issues that remain unsolved. Yesterday, we looked at a new high-school program trying to achieve what others before it have not. Today, in Part 3, we train the lens on teacher diversity.

Berkeley High School history teacher Dana Moran recently asked a classroom of seniors to count on their fingers the number of teachers of color they’d had during their four years at the school.

Not a single student needed more than one hand, she said.

“They were like, ‘It’s you and our Spanish teacher,’” said Moran, who is Asian-American.

This fall, Berkeley Unified is celebrating the 50th anniversary of voluntarily integrating its schools. Even back then, the school district recognized that the newly diverse classrooms demanded a diverse teaching force.

A (slightly sensational and a bit misleading) Berkeley Daily Gazette headline from 1969 read, “District seeking 444 black teachers.” In reality, that figure was the number Berkeley Unified aimed to hire over the next several years, accounting for turnover — but it was still a very unusual goal at the time.

Elsewhere, teachers of color were often unintended victims of Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court decision that found segregated schools unconstitutional in 1954. Black teachers who had found stable employment in segregated black schools were rarely hired on newly integrated campuses, or faced discrimination when they were.

“Many got pushed out of the profession,” said Cathy Campbell, president of the Berkeley Federation of Teachers. “As a country, we’re still trying to repair that damage.”

Studies have shown students of color are more likely to graduate and do better in school when they have a teacher who is the same race as they are.

Berkeley administrators actually traveled to the South to actively recruit black teachers, wrote then-Superintendent Neil Sullivan in his 1970 memoir “Now is the Time: Integration in the Berkeley Schools.” By 1968, about 18% of BUSD’s teachers were black — more than today.

The same issues around educator diversity have come up again with greater force lately, and this time the people ringing the bell are armed with research indicating they have a point. Studies have shown students of color are more likely to graduate and do better in school when they have a teacher who looks like them. In a district like Berkeley, which, like many others, has painful achievement gaps, those educators could make a difference, advocates say.

In Berkeley and the Bay Area, teachers are especially sensitive to circumstances resegregating neighborhoods, and a housing market making it challenging for anyone to live here on a public educator’s salary. In response, new efforts are emerging to support the teachers of color already working in Berkeley schools, and to push the district to hire more.

Berkeley teachers don’t reflect diverse student body

In Berkeley Unified last year, Latino teachers made up almost 10% of the certified staff population, and black teachers about 8%, according to the district. White teachers constituted a much larger 70%. According to data reported to the state, the Asian teacher population has hovered around 6-7% in recent years. That compares to a student body that is under 40% white.

Representation for teachers of color was a bit higher among the brand-new employees. Twelve percent of the new teachers hired for 2017-18 were black, and 11% Latino. Those numbers just exceeded a goal set by the district in its Local Control Accountability Plan — to have 22% of newly hired teachers be people of color.

Those figures still do not reflect the more diverse student population in Berkeley schools, but they do reflect the national teacher workforce.

“While a majority of the nation’s public school students are students of color, fewer than 20% of our nation’s teachers are teachers of color, and only 2% are African-American men,” wrote U.S. Education Secretary John King and Learning Policy Institute CEO Linda Darling Hammond in the Hechinger Report.

A growing body of research has found that students of color do better on tests, and are less likely to drop out, when they have teachers who look like them. The positive outcomes are more pronounced in black boys, who currently are mostly taught by white women.

An April 2018 report from the Learning Policy Institute offered an extensive list of studies demonstrating the power of a “race-matched” teacher for students of color.

Having a single black teacher in grades 3-5 significantly reduced a black boy’s chance of dropping out of high school, according to a study released last year by Johns Hopkins University, American University and UC Davis, which looked at 2001-2005 data from North Carolina. That effect was even stronger for low-income black boys. The study also found that having a black teacher had no effect on white children by these measures.

Some of the same researchers previously looked at 2006-10 data from North Carolina and found that K-5 students with teachers of another race, particularly boys of color with white teachers, were more likely to be chronically absent and had more unexcused absences.

An analysis of Tennessee test scores found black elementary school students with black teachers had slightly higher — by three to four percentage points —reading and math scores. In the long term, those students were less likely to drop out and more likely to take a college entrance exam.

Moran said she’s realized how starved some of her students are for identification with adults on campus.

Last year, she had two students who were children of Asian immigrants. They both told Moran she was their first Asian American teacher, and said she was their role model. One even joked about following her around all day and becoming her “best friend.” Moran said she was startled, especially because these students had backgrounds quite different than hers.

Moran grew up in Berkeley and was there in 1968 when the schools integrated and in the years following when a number of experimental programs were launched. She attended Franklin Elementary, where she went to an Asian-American program. The teachers were all Asian-American, and the classes focused on Asian history and languages, but the students were diverse, Moran remembers.

As a kid, she never stopped to think that all students weren’t learning Mandarin in fifth grade or taking class field trips to Chinese mining camps or temples in the foothills of the Sierra. She told the Berkeley School Board that the experience was likely what showed her she too could be a teacher, a dream she hung onto and accomplished.

“It’s not like they’re going to relate to every teacher who looks like them,” she told Berkeleyside. “But someone would be nice. It’s just kind of weird that they never see themselves represented in the adults on campus who aren’t safety staff.”

But representation is just part of it, said union president Campbell.

Having a non-white teacher “provides unique benefits for students of color, but it improves the learning for all kids. We believe having a more diverse teaching staff raises the level of discourse at school sites for everyone, all staff. In Berkeley we’re looking at equity gaps already, but having a more diverse staff creates more urgency around these issues, and creates cultural capital that white teachers can’t provide.”

Teachers: “Hire us earlier”

In 1995, BUSD administrators said explicitly that they used affirmative action in hiring decisions. A year later, California voters approved Proposition 209, prohibiting state institutions from considering race, ethnicity or sex in specific hiring or enrollment decisions. But the district today talks about improving the hiring process to at least make it more accessible to candidates of color.

“When we set a goal such as 22% teachers of color, that is not a quota, it is a benchmark for us to look at to see if we are succeeding in attracting more diverse staff,” said Evelyn Tamondong-Bradley, assistant superintendent of human resources, in an email to Berkeleyside. “In terms of hiring, we do not consider race in assessing an individual’s qualifications — we are looking for the most qualified candidate, and are pleased that we have been able to attract more teachers of color to apply and qualify.”

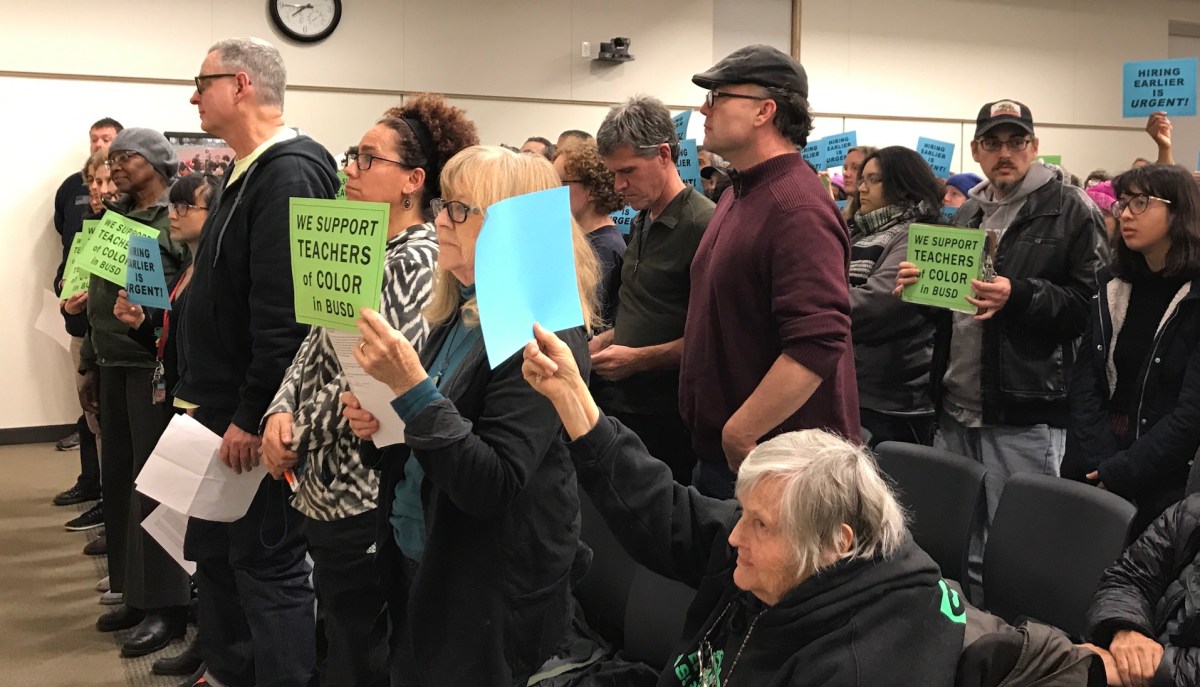

At a January 2018 Berkeley School Board meeting, a number of teachers delivered coordinated pleas for a diversified workforce, particularly imploring the district to start its hiring process earlier in the year. They said qualified candidates, especially star teachers of color, were getting snatched up by neighboring districts that got the ball rolling earlier. Many held up bright blue signs that said, “Hiring earlier is urgent!”

They also asked to include more standardized practices that bring out qualities in candidates who might not look impressive on paper, like bringing them into classrooms for sample lessons, which only some principals do currently.

Tamondong-Bradley said she supports that practice.

“When I was a principal I had mock lessons. It was incredible to just walk in and watch them command a room,” she said.

The district has been working with a consultant, Kacy Robinson, to improve practices around teacher recruitment, retention and equity. BUSD did end up starting the hiring process sooner for this year’s new teachers, said Tamondong-Bradley. Previously staff waited to recruit and screen job candidates until they knew exactly which positions would be vacant — sometimes as late as summer — she said. The district began soliciting candidates this past spring, even though it wasn’t clear who exactly would be leaving when the year ended.

Another big barrier to hiring everyone Berkeley Unified would like to, multiple people have told Berkeleyside, is simple bureaucracy — the district still uses paper forms. That slows down the process significantly, creating more opportunities for candidates to accept jobs from districts that long ago entered the digital age. BUSD staff say digitization is a goal for this year but it’s time-consuming.

Despite the difficulties, Berkeley’s school year started with hardly any vacancies, something many other districts can’t claim. In Tamondong-Bradley’s view that’s a testament in part to the hustling staff did to get new teachers on board. It is also a sign that BUSD is still a desirable district for new candidates — including many who attended Berkeley schools themselves. BUSD is also much smaller than, say, Oakland Unified.

It isn’t easy work, though, with teacher shortages across the board, and few teachers of color coming out of credentialing programs, said Tamondong-Bradley. Science, math, bilingual and special-education positions are hardest to fill.

“Barriers to recruiting teachers of color exist at each stage of the teacher pipeline, beginning at the K-12 level,” where students of color are less likely to graduate or have high test scores, wrote Desiree Carver-Thomas, author of the Learning Policy Institute report.

Once they get through college, black students graduate with far greater student loan debt, on average, than their white peers, so they may be less likely to pursue post-secondary education or enter the low-paying teaching profession. A far greater percentage of people of color enter teaching jobs through alternative pathways, not traditional teacher preparation programs. Those employees are often less prepared than new white teachers and might not have the student-teaching experience they would have gotten in graduate school.

Carver-Thomas says there are a number of steps states and districts can take to reduce these barriers — from loan forgiveness programs and teacher-training residency programs, to assembling diverse hiring committees, partnering with minority-serving institutions, or giving incentives encouraging teachers who are retiring or quitting to announce their decisions earlier in the year.

New in Berkeley this year is a program helping some of Berkeley’s classified staff get teaching credentials. These “grow your own” programs have gained traction in recent years as a way to help certify staff, like instructional aides, who may have extensive experience in an educational setting but who haven’t previously had the funds or time to take off and go to school.

Berkeley’s program is supported by a state grant, and this year provided 12 employees — from custodians to classroom aides — with $4,000 scholarships they can use on tuition reimbursement, credentialing fees or books.

“The expectation is that they will commit to work for BUSD upon completion,” said Brent Daniels, director of human resources. “We want to hire staff that have a strong understanding of the needs of students.”

The program could help diversify Berkeley’s teaching force, as there is a larger percentage of classified staff of color.

The district also provides “cultural competency training” for teachers, designed to make educators more aware of implicit biases, and how to serve potentially unique needs of black students and English learners.

Campbell said that’s the best step the district can take beyond hiring teachers of color, even though “it may seem counterintuitive,” is to invest in programs for white employees. “Next would be to invest more time and energy in helping all of our teachers navigate parent engagement,” she said.

This past summer, a three-day training offered to K-8 teachers who had not taken the workshops in the past covered how power dynamics and white privilege play out in the classroom, and offered instructional techniques to reach diverse students.

Many black students and families in Berkeley — although it’s a national phenomenon — talk about feeling misunderstood or immediately written off by white teachers, who they feel either have lower academic expectations of black students than they should, or hold them to higher behavioral standards. The Learning Policy Institute report noted that studies have shown teachers of color typically have higher expectations for students of color than white teachers do.

At a recent meeting of the Parents of Black Children Collective, an advocacy and support group of Berkeley parents, who also fundraise for a scholarship, many mothers talked about feeling like their kids’ academic potential was dismissed by educators, who didn’t push them hard enough, or that their kids were sent to On-Campus Intervention or suspended to be “gotten rid of.”

Although the district overall got the second-to-best mark (out of five) for its suspension rate on the California School Dashboard, it got the second-to-worst grade for its African American suspension rate.

Several of the parents said they routinely introduce themselves to the children’s teachers at the beginning of each year, signaling: This student comes from an educated family with high expectations of our children that we hope you share.

“A white student is failing and a teacher takes them to the side, and calls up their parents. Let’s say Tyriece in sixth period is doing the same thing, and the teacher just says, ‘That’s what’s expected.’”

“It seems weird that you have to go humanize your child,” said one mother, who didn’t want to be named.

Many public educators in Berkeley and beyond care deeply about social justice and believe in the potential of all children — there are few reasons to go into the low-paying profession if you do not — but research has repeatedly affirmed that most people, not just in education, possess implicit biases.

Jahlil Rahim, a 2018 graduate of Berkeley High, who started a club for black male students there, said that to him, it looked like his black peers were regularly, and harmfully, misunderstood.

“From my experience, I would say that a lot of the teachers don’t know how to deal with black students,” said Rahim, now a freshman at Howard University. “A lot function off of assumptions. They don’t take the time to understand why a student might be acting a certain way. There’s always a lot of factors going into why any child isn’t 100%, academically. It could be that a white student is failing and a teacher takes them to the side, and calls up their parents. Let’s say Tyriece in sixth period is doing the same thing, and the teacher just says, ‘That’s what’s expected.’”

Rahim takes issue with the labeling of students of color as “at-risk.” The phrase is typically used by concerned and thoughtful educators to justify and target academic support, funding and programs at students who statistically are more likely to drop out or fail. But to Rahim, and to many educators in Berkeley who have stopped using the phrase, it “pushes this inferiority complex among young men that are pretty impressionable.”

Teachers and administrators have tried to create structures that squash biases and inequities, introducing more cultural-competency training and creating programs like the universal ninth grade, where teachers are better able to truly get to know students and collaborate to offer them support.

Rahim, who has attended schools in multiple states, said he is cynical about the potential of programmatic changes to make a real difference.

The answer, in his view? “More black teachers.”

Trying to keep teachers of color in Berkeley

Hiring is just the first step, teachers say.

The next is making sure those teachers stay in the district.

“Retention and recruitment are integrally linked,” Campbell said. “If you recruit a teacher but they’re the only black teacher at the site, they’re not going to stay. There’s still a fair amount of isolation.”

She and some of her union members launched the Teachers of Color Network in 2007 to create a supportive group, and advocacy tool, for the educators spread out among different campuses. The network has pushed the district to make teacher diversity a priority.

Shannon Erby, a Berkeley High history teacher and a Teachers of Color Network facilitator, said she’s heard often from members of the group that Berkeley schools are still appealing to candidates of color.

“There’s creativity with curriculum. There’s certainly access to resources that not all districts have, like a new-teacher budget,” Erby said. The network tries to help those enthusiastic teachers stay happy once they’re on board. It’s also a social group, gathering teachers for picnics and happy hours. A Leaders of Color Network exists for administrators too.

“The same thing we talk about with students — needing to feel camaraderie amongst themselves — the district should look at for staff,” said Kamar O’Guinn, manager of the BUSD’s new African American Success Project.

Many teachers who are isolated at their schools have described feeling the burden of a so-called “invisible tax.” They’re asked to speak on panels and asked to talk to parents — asked to take on extra tasks that their white peers cannot, or to be the token person of color at a school event.

“Years ago, when the black history teacher left, I got a phone call asking me to take on the black history department,” Erby said. “When some of the racial incidents have come up, I feel like I need to be there for the kids. Other teachers care and love them too, but don’t have the experience of being called the n-word and what that does to your soul.”

When does the race of a teacher matter? Ask their students

In 2016, the Berkeley chapter of the NAACP wrote a memo asserting that top BUSD administrators and the Berkeley High principal at the time were “engaging in a process of ethnic cleansing of African American employees.” In the letter, chapter President Mansour Id-Deen listed a set of grievances, including a lack of transparency and a hostile attitude toward staff, improper training of safety staff or substitute teachers, “retaliation” against African American employees who criticize the district, and “most importantly” a lack of programs targeted at struggling African American students.

The district has since taken some of the steps outlined in Id-Deen’s letter, like creating a new program and staff positions dedicated to African American students who are struggling. Some specific administrators he criticized no longer work for the district.

Some of the complicated and sensitive discussions that have arisen about individual teachers in the district in recent years mirror large national questions about just how much race should be taken into account in personnel decisions — and whether salaries and teacher training programs are set up to attract qualified candidates of all races.

And is it inherently better for an educator of color to teach certain subjects? Or is that limiting, closing doors to highly knowledgeable teachers equipped to lead Latin American history regardless of whether they’re from the region themselves?

Berkeley High School ninth-graders asked themselves these questions in recent a recent seminar discussion in an ethnic studies class.

Students were asked whether ethnic studies should be a national graduation requirement, like it is in Berkeley. Some of the teenagers wondered aloud whether the race of the educator leading the course mattered.

It was white students who argued most vocally for teachers who identify with the cultures they’re teaching about.

“If it’s targeted toward a specific group, like African Americans or Mexican-Americans, it needs to be taught by a member of that group. Students are going to be a lot more inclined to listen and learn,” said a white girl in the class.

“That’s like saying you have to have a math professor teaching math. You can be knowledgeable about something that’s not happening in your day-to-day life,” said a white boy.

“It should be someone who has more empathy and relates to the struggles and successes of the people you’re teaching about,” countered another.

One white boy wondered whether there would always be enough Mexican-American teachers in an area to fill those positions.

Students felt a course was only as good as the teacher leading it.

“I’m pretty sure there are,” a Latina girl responded. “If there’s a teacher who’s an immigrant and has been through that kind of experience, he or she probably knows better.” If it was a class about a specific culture, she said she’d like to see that represented in the teacher, because “they actually understand.” But for a general ethnic studies class, she said it’s only important for the teacher to be good.

Throughout all the discussions in two class periods that day, one thing was clear: students felt a course was only as good as the teacher leading it.

O’Guinn said he’s well aware of how even one adult who “gets” a student and tracks their success can be turning point. That’s one of the goals of the new African American Success Project he leads, with stations full-time staff at the high school and middle schools.

“This gives students someone they can count on at the school site. Teachers and counselors are well-intended, but their time is limited,” O’Guinn said. “Particularly at the high school, you can refer students to tutoring, but who has the time to really dig down and call the family, and make sure they’re going?”

O’Guinn thinks all districts, and particularly those in the Bay Area, will continue to have challenges recruiting and hiring more teachers of color until salaries can cover a lot more of their mortgage or rent.

Some teachers have posited that with demographics changing in the district, teachers of color might not even want to work at Berkeley schools in the first place. But O’Guinn said the last school he worked at, which had hardly any white students, had exactly the same challenges.

Like the Berkeley High freshmen in their seminar discussion, O’Guinn said adults on campus make the difference when it comes to boosting student achievement and engagement, and reducing racial disparities.

“We tend to think big and broad about how we solve this problem,” he said. “It boils down to having someone at the school site that says, ‘I’m not going to let this student fall behind. We won’t let you fail in life or in school. Whatever’s happening at home or in school, let’s make you successful.”