Update, Feb. 10 The man suspected of killing Gene Ransom has been charged with murder by Alameda County prosecutors, according to charging documents provided by the Alameda County District Attorney’s Office.

Prosecutors have charged Juan Angel Garcia with felony murder and felony use of a firearm, along with other charges.

Garcia allegedly pulled up next to Ransom’s vehicle driving northbound on I-880 and shot him in the head, killing him, according to a probable cause statement for Garcia’s arrest. Ransom’s car then crossed several lanes of traffic and crashed into a cement wall.

Original post, Feb. 8 Berkeley basketball legend Gene Ransom, one of the most successful basketball players to come out of Berkeley High, died Friday night in a shooting on Interstate 880 in Oakland. He was 65.

Ransom was heading to visit his girlfriend in West Oakland on Friday evening, according to longtime friend and Berkeley High graduate Doug Harris. The driver was northbound on I-880 in a Honda Civic when someone in a black Lexus sedan pulled up next to him and opened fire, the California Highway Patrol said in a statement. The Honda hit a guardrail near the Oak Street exit. The driver, whom friends and family have identified as Ransom, died at the scene.

Police arrested Juan Angel Garcia, 25, on suspicion of murder Saturday morning. Oakland CHP says the motive is under investigation.

Standing at just 5 feet 9 inches tall, Ransom became a three-sport legend at Berkeley High, excelling in baseball, football and basketball. What he lacked in height he made up for in quickness and an intimate knowledge of the game. “When the chips are down, Ransom is the man the Jackets look for and other teams know they have to stop him,” sports reporter Mike Hall wrote in a 1974 issue of the Berkeley Gazette.

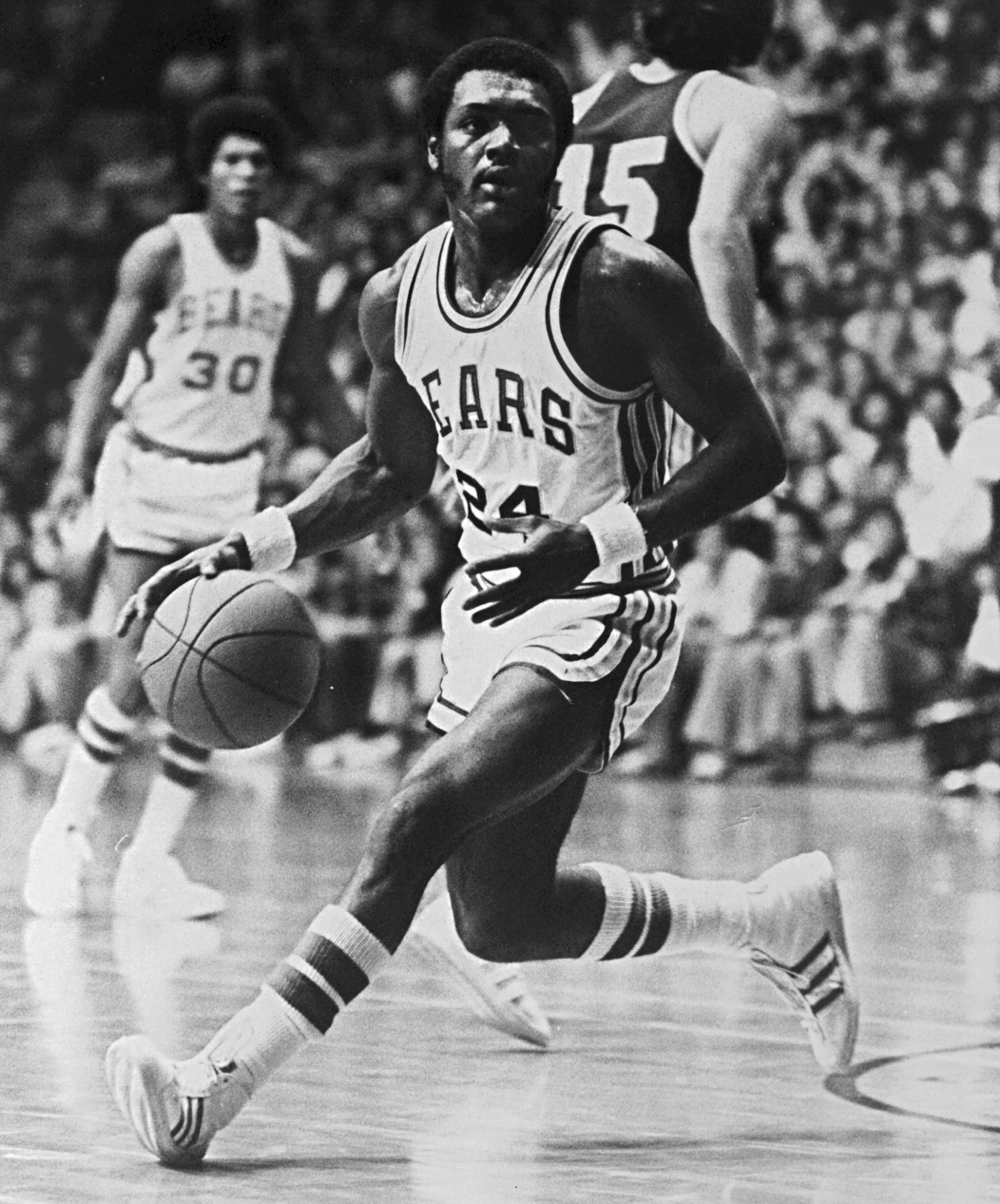

Known for deftly passing the basketball to teammates, Ransom went on to play three years for the Cal Bears. He led the team in assists for all three of those years before transferring to the University of Nevada, Reno. Ransom was inducted into Cal’s Hall of Fame in 2001.

When Ransom was at his best, he could electrify the crowd, one night playing for nearly 64 minutes straight at Harmon Gym, a Bears record.

When Ransom made it to the NBA after college, Oakland Tribune writer Ron Borges described the rookie player as “a Lilliputian trying to survive in a world of walking redwoods.” Ransom told the reporter that his goal to start for the Warriors was motivated by a community in Berkeley that had believed in him, despite skepticism from the basketball world.

“I have always had to prove I could play.” — Gene Ransom

“They have always told me basketball is a big man’s game. I have always had to prove I could play. They said it in high school and I did it [started for the team] as a sophomore. They said it in college and I did it. Now they all wonder if I can play as a pro,” Ransom told The Tribune.

Ransom signed with the Warriors in 1979, but he was cut after one game. He switched to baseball, playing in the Oakland A’s minor leagues for three years before retiring from professional sports.

Ransom later became a mentor to young players in the East Bay, coaching the Berkeley High Jackets for two years and starting a travel team called Reach Your Goal. Like his father, he worked as a longshoreman at the Port of Oakland.

“He worked tirelessly to help provide something positive for the community that he was a product of,” Harris said of Ransom, who was the godfather to Harris’ daughter, Chantelle, and whom Harris called his “little big brother.” Days before he died, Harris and Ransom had made plans to play three-on-three over the weekend.

“The very thing that we worked so hard for is what killed him — senseless gun violence,” Harris said.

Ransom’s Berkeley roots

Born Horace Eugene Ransom on Jan. 21, 1957, Ransom moved from Fresno to Berkeley as a young boy. He grew up in West Berkeley, developing his basketball style on Berkeley playgrounds and at the local YMCA.

Looking for a basketball hero, Ransom watched a trio of Berkeley basketball stars — Doug Kagawa, Carl Shelton and Phil Chenier, who went on to play 10 seasons in the NBA — play 3-on-3 at the basketball courts near Columbus Elementary, now called Rosa Parks.

Ransom shadowed Chenier, who was notoriously quiet, trying to pick up on his game. “I’m a young kid idolizing you, waiting for you to just say hi,” Ransom joked during a 1993 speech at Jack London Square in Oakland dedicated to roasting Chenier.

“The reason why I was a pretty decent basketball player was because I studied you,” Ransom told Chenier. “I tried to emulate that jump shot all the way to Cal.”

When Ransom started playing for the Jackets his sophomore year at BHS, he quickly garnered the attention of the local and regional press, filling stadiums with local fans eager to watch the kid play.

“Gene is the only person that I know that they could sell out the Oakland Coliseum for a high school basketball game,” said Harris, a filmmaker who has captured Ransom’s accomplishments, along with those of many other athletes, on camera. Sports journalists started calling the rising Berkeley star a nickname that followed him throughout his career: Gene “the Dream” Ransom.

“He was very astute about how the game would be played,” said Jim Skeels, who played with Chenier at Berkeley High and later became Ransom’s baseball coach and friend. Skeels said Ransom knew how to pass and handle the ball with flair, shifting it from one hand to another in mid-air. It was those skills that carried him through three seasons at Berkeley High, where he earned the all-Tournament of Champions title three years in a row and was named Nor-Cal Player of the Year in 1974, and onto his record-breaking time as a point guard at UC Berkeley.

When he graduated, BHS yearbook staff wrote that Ransom’s “athletic achievements could fill an entire yearbook,” adding: “In a school with the diverse and immense talent that BHS has, only a superlative person could stand out above the rest,” one caption reads. “Gene Ransom is such a person.”

The Berkeley community that supported Ransom

In the last few months, Ransom had started talking about having a book written about his life, recounting to friends the themes and stories he thought should comprise the biography’s centerpieces.

Berkeley featured prominently in the stories of Ransom’s coming-of-age, both its overall character and its many individual characters.

Coming to the city as a farm boy from Fresno, Berkeley’s multiculturalism and progressive attitude left an impression on the young Ransom.

“He talked about what Berkeley represented to him,” Skeels said. “It was very eye-opening to him that these people all got along and the racial mixtures were unlike anything he had ever experienced.” Gregarious by nature, Ransom would light the room at a party and made friends with a wide range of people.

In Ransom’s mind, the biography was as much about the Berkeley people who shaped him as it was about his own life. Ransom wanted to feature his personal heroes in the book, from players like Chenier who inspired him to the adults who mentored him and provided opportunities.

Ransom spoke often of Johnny Birch, a basketball coach and educator at Peralta Community College District. Birch took Ransom under his wing, driving him to play with high schoolers to help him improve his game when he was barely a teenager.

And there was Calvin Anderson, a counselor who shepherded Ransom through high school, helping him meet the requirements he needed to matriculate to UC Berkeley.

Legend has it that Anderson challenged ninth-grade Ransom to a game of ping-pong, betting that, if he won, Ransom would need to request that Anderson become his college counselor. “Anderson smoked him,” Harris told Berkeleyside with a laugh. The counselor provided academic guidance to Ransom throughout his high school career.

During the speech roasting Chenier, Ransom delivered a prescient message.

“I would like to take this opportunity to say thanks, man. Because sometimes people wait too late to say thanks. After somebody passed, you say, ‘I wish I would have said thank you.'”

Giving back through basketball

After his career as a basketball player ended, Ransom started looking for a way to give back to the community he loved. Though he played college ball for four years, he never earned his bachelor’s degree. He took odd jobs for a few years, working as a house painter, and eventually found steady work as a longshoreman at the Port of Oakland, following in his father’s footsteps.

“It was always a struggle to create an identity outside of [basketball], while incorporating something that he loved, but not being defined by it,” said Paula Gerstenblatt, who met Ransom when he was coaching her son at Berkeley High and began a relationship with him that lasted two decades.

His time as a competitive basketball player came to be synonymous with Ransom’s identity, even when Ransom himself had moved on. Gerstenblatt said they’d be at a gas station when someone would recognize him and call out, ‘Hey, dreamer’: “That was eight years of his life. That wasn’t the sum total of who he is.”

Gerstenblatt described Ransom as something of a homebody, happy to stay home with their “pack of dogs,” which consisted of a Labrador and three golden retrievers. He loved Mexican food and enjoyed relaxing at Stinson and Muir beaches in Marin County. “That was enough for him,” Gerstenblatt said.

Eventually, Ransom started working with young players, a position in which he really shined. “The real joy was in helping young people, aspiring athletes, develop,” Gerstenblatt said.

In 1999, Ransom was hired as a basketball coach at Berkeley High, where he led the freshman boys team to a 27-0 record.

But two years later, the high school chose someone else over Ransom as the head coach, a decision that Gerstenblatt said was “very painful” for Ransom.

Hoping to continue the coaching work that he loved, Ransom started Reach Your Goal, a traveling club team that was geared toward getting young players recruited by colleges. The club cultivated excellence in basketball and also required players to read and do community service with Head Start, a youth support program focused on vulnerable families.

As a coach, Ransom was intense and nurturing, according to former player Doni Noble. “He demanded a certain level and that became the baseline for our team. We played with fire and intensity that was directly from him,” Noble wrote in a text message to Berkeleyside.

“One thing I can remember is I never felt like I was just on a team and it was just about basketball. It felt like a family,” Noble wrote.

Ransom’s club team members describe a coach who paired basketball tips with life lessons. Devin Peal remembers Ransom telling the players about the journey his own life had taken him on, and how he eventually committed to getting his degree. After decades without a college degree, Ransom eventually went back to school and got his diploma from New College of California.

After getting a job as a longshoreman, Ransom was unable to juggle both gigs, choosing to leave the club team behind.

But Ransom still found a way to work with young people.

Partnering with Harris from 1990 to 2012, Ransom became a mentor to young men in Berkeley through Athletes United for Peace, a nonprofit organization that provided healthy alternatives for those caught up in street violence.

On Friday nights, the basketball court became a haven with Ransom standing on the sidelines, arms crossed, offering guidance to players ranging from how to improve their jump shot to how to get their GED.

“Gene gave them the type of real guidance that these young people needed, that they weren’t getting out on the streets,” Harris said. With Ransom gone, Harris hopes that someone else will take up the baton and become a mentor to Berkeley’s youth.