The 61-year-old man convicted of fatally shooting a 19-year-old UC Berkeley student he’d spotted on the street told the teenager’s family, during a sentencing hearing Monday, that he was remorseful but had “no reason” for what he had done.

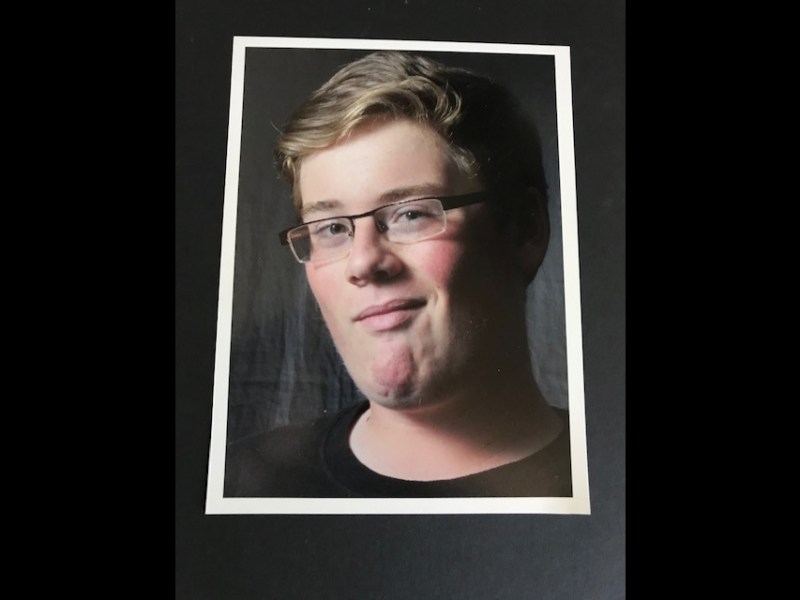

A scholarship fund in Seth’s memory remains open, one of several ways his family is keeping the young man’s memory alive

“You got so many innocent people out here dying,” Tony Walker told Seth Smith’s family and best friend during the late-day hearing. “And here I am, I’m going out committing murder on innocent people. And it’s just not right. I don’t care who does it. It’s no reason for it. I don’t have any reason. I don’t have no justification.”

Walker’s statement was part of a surprise plea deal reached in the case earlier this month. As a result of the agreement, Walker was convicted of voluntary manslaughter and sentenced to 25 years in state prison. He also agreed to make a direct statement to Smith’s family to explain what he had done.

But Seth’s mother, Michelle Rode-Smith, told Berkeleyside the statement felt “incomplete.”

“Was it simply, he walked by you randomly and you just saw him as prey? I don’t know that,” she said after the hearing. “What led him to be outside? He didn’t really explain that.”

Walker’s statement was short on details about the night of the killing on Dwight Way on June 15, 2020. He said only that he had gone outside to clear his head “and, before you know it, I shot Seth.”

“I couldn’t believe it,” Walker continued. “He didn’t do anything to me. He didn’t deserve it.”

Walker also told the Smiths he was “not a violent person.” But his criminal record tells a different story. As an adult, Walker racked up 11 felony convictions, including several for robbery, according to court records reviewed by Berkeleyside on Monday. He was sent to prison three times between his early 20s and early 40s.

Walker was on probation for illegal gun possession when he killed Smith.

“The defendant has established an entrenched pattern of criminal conduct that probation, prison and parole have been unable to eradicate,” a probation officer wrote in a recent assessment of Walker. “During his 50-year criminal history which began at the age of nine, the defendant has amassed eight findings, 15 convictions, multiple grants of probation, and multiple prison commitments. Sadly, at age sixty-one the defendant is still not prepared to shed his criminal lifestyle.”

Walker had been placed in foster care at age 9 after being caught stealing and “deemed incorrigible.” He spent many of his formative years in juvenile hall and the California Youth Authority in connection with a range of criminal offenses, including a robbery at age 16.

Walker was born in Missouri but grew up in Berkeley with his mother and four siblings, according to the probation report. His father was incarcerated until he was 12. The next year, Walker’s mother died from complications related to diabetes and the family was “dissolved”: The children were sent to various locations “including juvenile detention facilities.”

Walker said his upbringing was unstable because he was in and out of so many institutions. But he said it wasn’t violent and that he was treated well both at home and in the other places he lived. He described his mental health as “satisfactory,” according to the probation report.

The probation officer found no mitigating circumstances that would justify a lighter sentence.

“The defendant has demonstrated that he is a danger to the community and needs to be separated for the community’s protection,” the probation officer wrote.

“I was going through a lot,” killer says

On Monday, Walker was visibly emotional throughout his statement, at times choking up or crying. When it was his turn to speak, he paused for nearly 30 seconds, then exhaled quickly, blowing a stream of air through his lips.

“I know whatever I was gonna say ain’t gonna change anything,” he said. “I never killed nobody in my life. I never intended to kill Seth. I was going through a lot of deep-seated things in my life.”

EXCLUSIVE: Read more about the evidence in the case against Tony Walker

He then said his parents had passed away — although his mother died in 1972 and his father in 2007, according to the probation report.

“I was feeling alone and isolated due to COVID,” Walker said. “I never intended to go out and hurt anyone. I wasn’t raised like that. My mother didn’t raise me like that.”

He also said he had never read any books that encouraged or advocated for the killing of innocent people.

“I’m not that type of person in my heart,” he said. “I’m truly sorry. I feel so remorseful.”

Walker said he prayed to God every night, and that he prays to Seth, too.

“I ask him, if he can hear me, to forgive me for taking his life,” Walker said. “He had much more going for himself than I did.”

Walker described himself as a “washed-up nobody” who probably deserved to die in prison.

Walker’s comments followed victim impact statements read by Seth’s mother, aunt, uncle and best friend, and their words appeared to have struck a chord: “I didn’t know he had all that going for him. I didn’t know him, period.”

Walker also said Seth was innocent, and “undeserving of what he got.” He quickly corrected himself, adding “what I done to him.”

“My life is over,” Walker told the Smiths. “Seth had a long life ahead of him, and a bright one, a fruitful one. It just wasn’t right for me to do what I did.”

In closing, he said he hoped the family would find a way to forgive him.

“If you don’t, I truly understand,” he said. “I don’t know if I could forgive someone in this situation.”

As the hearing ended, just before a deputy led him out of the courtroom, Walker addressed the family once again.

“Bye, Mrs. Smith. God bless you guys,” he said, raising his fist into the air in front of his shoulder. “Keep strong.”

Keeping Seth’s memory alive

On Tuesday, Seth’s mother told Berkeleyside that Walker’s statement had done little to comfort her.

“He took my kid for no reason,” she said. “We all go through some things. I don’t go shoot a stranger in the street. Forgiveness is not something I’m willing to give him.”

Rode-Smith said she is, however, working to forgive herself. Throughout the grieving process, she has questioned what she might have done differently: Was there anything she could have done to keep her son alive?

Just before Seth was killed, he had been planning to go home to the Sacramento area. Classes had ended for the semester. But he decided to stay in Berkeley to go hiking with his new roommates.

“I should have made him come home the weekend before this happened,” Rode-Smith said, adding that she is also trying “to forgive myself for the anger I feel and … for not being there to protect him.”

She said she had also grappled, on some level, with the fact that Seth had been walking alone at night when he was killed. He was wearing earphones and was likely listening to music, perhaps dancing at times, as he ambled down his own street about a mile from his house.

The court had identified Smith as a vulnerable victim, in part because he was wearing earphones — “inattentive to his surroundings” — when he was killed. He was approached from behind and died instantly when Walker shot him once in the back of the head.

Rode-Smith said Seth had always felt safe in the world, a quality she had encouraged and admired in her son. But now, she sometimes questions that too.

“Maybe I should have made him more afraid,” she said. “But we shouldn’t have to. No one should have to tell their kid that.”

The family and community have done a number of things to keep Seth’s memory alive in the nearly two years since his killing. There is a scholarship fund open on GoFundMe: Two young people have already received help paying for college as a result of it.

Seth’s elementary school in Elk Grove, where Rode-Smith is a fourth grade teacher, is planning to rename its library in his memory. By the time he had finished sixth grade, he had read every book in the place.

“The library was his home,” his mother said.

Aunt: “This is not a story where wishes come true”

Kim Rode, Seth’s aunt, is planning to establish a summer drama camp inspired by Seth’s love of theater. A dressing room at his high school has just been named in his honor. The family also hopes to establish a nonprofit organization in his memory.

“While we have done our best to turn this into something positive in memory of Seth, we really just want him back,” his uncle, Jackson Collier, told Judge Kevin Murphy on Monday. “There is a Seth-sized hole in our family.”

When it was her turn to address the court, Rode described her nephew as kind, always appreciative and downright brilliant. He was fully reading by 4 and was already reading chapter books by the time he was 5.

“In a family full of educators, academics and over-achievers, he stood out as the brightest young star in our midst,” she told the judge. “It wasn’t long before it was apparent that, as smart as his parents were, this kid was smarter. Many of his teachers through the years were challenged by him and several admitted at a memorial for him shortly after his death that he was smarter than them — and they knew it.”

Smith had dreamed of attending the London School of Economics after graduating from UC Berkeley with a double major in economics and politics. He had entered Cal as a second-year student because of all the AP courses he’d gotten credit for in high school. And, though he was only 19 when he was killed, he had just one more year before he would have completed his studies.

“I wish Tony Walker wasn’t on the street that night. I wish he hadn’t gotten a gun, since he was legally prohibited from having a gun or ammunition,” Rode said during Monday’s hearing. “I wish Seth had not walked down that street. But mostly I wish Seth was here with the family that loves him. Sadly, this is not a story where wishes come true.”

In addition to Smith’s family and best friend, the only attendees at Monday’s hearing were two Berkeley police officers and Berkeleyside. Smith’s father has not appeared in court because the loss remains too difficult for him to bear.

No one attended on Walker’s behalf.

Seth’s mother cried quietly through much of Monday’s 30-minute hearing. She told Berkeleyside she continues to struggle with strong emotions.

“There are good days and bad. Some days I can talk just fine and I can tell stories about him and things we did together and laugh,” she said. “Then there are days when I just drive in the car and think about him, crying all the way to work.”

There are fewer of those days now than there once were.

“For the first several months, I cried every day. But I’m working on it,” she said. “When you have a kid, they’re a piece of you. They’re part of your heart.”