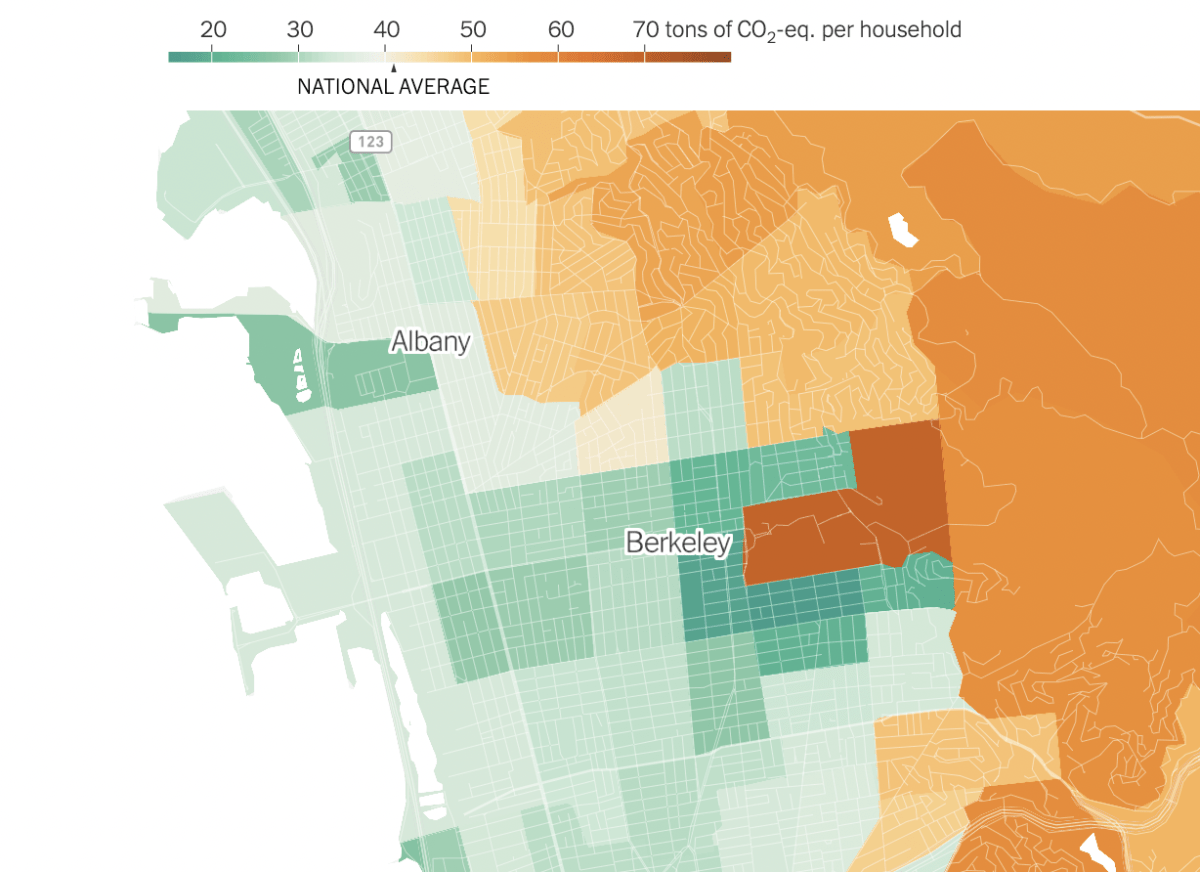

Households in the Berkeley Hills and parts of North Berkeley and the Elmwood are generating more of the greenhouse gasses heating the planet than the average American household, according to a new data study from UC Berkeley researchers.

UC Berkeley’s CoolClimate Network looked at energy consumption across five categories — transportation, housing, food, goods and services — and created a model estimating emissions for census tracts across the country. EcoDataLab, a consulting firm working in partnership with Cal, produced the data, which The New York Times turned into an interactive map. The data are not a direct measurement of consumption and include some estimates based on demographic, regional and national averages.

If you’re wealthy, you tend to buy more things, travel to more places and live in bigger homes requiring more energy to heat. But just as important — even more important — to your emissions footprint, the Cal researchers found, is whether you live in a dense urban area where you can walk, bike, take public transit, or just not drive quite as much as you would in the suburbs. Neighborhoods around big college campuses like UC Berkeley, where everything is close and walking common, tend to have low emissions.

Transportation and residential gas are the two largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions in Berkeley’s annual, production-based inventory, which, unlike the Cal study, only counts emissions released within the city’s borders.

The Cal study also identified housing and driving as the two biggest factors behind most households’ emissions. Houses in the Berkeley Hills are bigger, emptier and harder to get to than homes elsewhere in Berkeley, and the study shows hills residents tend to contribute more emissions related to heating their homes and filling their cars than people in the flats. Berkeley Hills households’ overall emissions footprints are on par with the national average for the categories of transportation or housing, according to the model. (When it comes to housing, this is mostly because California has cleaner electricity than the national average, said Ben Gould, the president of EcoDataLab.)

In the categories of services, goods and food — such as meat-heavy dinners, new clothes, and the possessions to fill their bigger homes’ many rooms — Berkeley’s wealthier, high-emitting neighborhoods tend to emit at rates higher than the national average, according to the model. (Food emissions do not scale as much as goods or services, Gould said, since there’s a limit to how much anyone can eat, though wealthier households still tend to be responsible for more food-related emissions.)

The researchers note that actual emissions numbers vary depending on lifestyle. A Berkeley Hills resident who uses solar panels or heat pumps or never goes on trips may have an emissions footprint well below average; a West Berkeley resident driving a gas guzzler to their job in Palo Alto may have higher emissions.

The intention of the study isn’t to blame individuals, said Gould, who also serves on the city’s environment and climate commission.

“Individuals make the best choices they can based upon their environment and the options available to them, which is shaped by governments and businesses,” Gould wrote in an email. “Our primary focus with this approach is actually working with governments, to help them change policies in order to make more and better options available to individuals.”

Most people in the U.S. don’t have the option to take transit or bike to work, use zero-emission electricity, or buy low-emission goods and services, Gould said, and in that regard, Berkeley’s actually doing better than most.

Still, there’s room for growth.

The study is an opportunity for city leaders to think about ways to address emissions “that occur outside of city borders, particularly around food, goods, and construction,” Gould wrote in an email. “The consumption-based approach helps cities to understand the relative impact of these categories in comparison to other ones that are more traditionally under their direct influence, such as transportation and building energy.”