Maria Boone Cranor — luminary female rock climber, co-founder of Black Diamond Equipment, and lecturer in physics at The University of Utah — died of cancer on Jan. 15, 2022, at the Salt Lake City home of her great friends April and Dale Goddard. She was 76 years old.

Maria grew up in San Francisco, the oldest of five. From the start she was the leader of the pack — bold, adventurous and creative. Her siblings followed her everywhere, even when it might have been wiser to stay home. She led them to the bluffs above San Francisco’s China Beach, where they scrambled along vertical cliffs, much to the dismay of her parents. However, Maria’s fierce spirit could not be contained. A precocious reader, she began school at the age of 4 and graduated from high school at 16 having read Tolstoy and Dostoyevski and become fluent in French.

She studied anthropology as an undergraduate at UC Berkeley from 1963-68 in the heyday of the Free Speech Movement, the Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam War protests. She attended marches led by Mario Savio and attended rallies where students put flowers in the bayonets of the National Guard sent to quell the dissidents. By her own account, she was transformed by her time at Berkeley, and left the university intellectually challenged, energized, and committed to progressive politics.

Despite the cliff scrambling of her youth, Maria was not much of an outdoorsy person. That changed in her early 20s, when she met her first husband, Carl Cranor, during her annual family vacation to Yosemite. They hit it off. For their first date, he took her hiking along the south fork of the Merced River. She wore cowboy boots and came home with horrible blisters. However, she quickly became devoted to the outdoors, and was introduced to rock climbing by one of Cranor’s friends. She was instantly hooked.

“Nancy and I stuffed our packs into my tiny hatchback,” she wrote in a 2010 essay for the Patagonia catalog, referring to her lifelong friend Nancy Henderson. “We picked out some routes we thought we could do and we were primed for our first trip to the valley — girls on the loose with rope, rack, and, we hoped, the chops to hold our own at the epicenter of the climbing universe.”

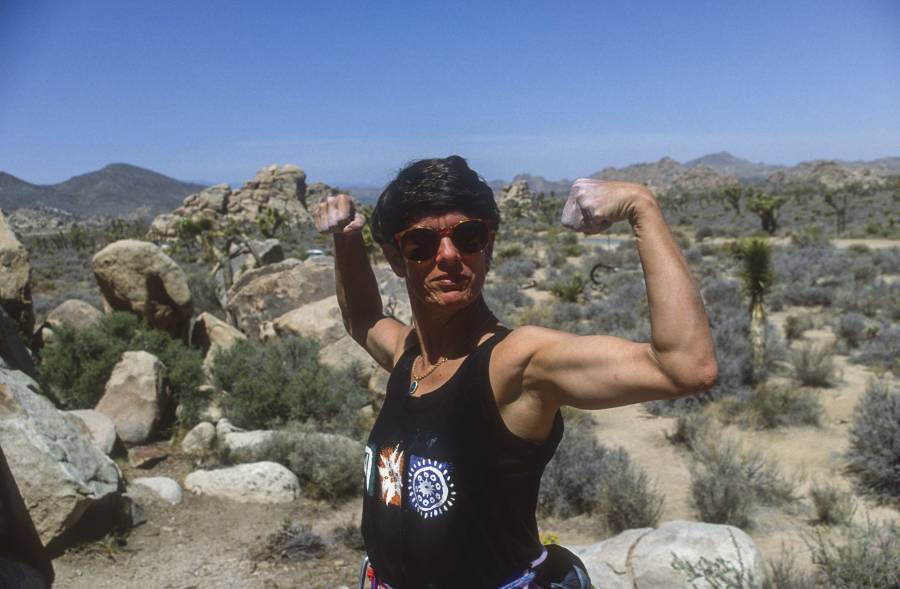

It wasn’t long before she proved to herself — and everyone around her — that she had the chops. Maria became central to the new era of “clean” free climbing in the Yosemite Valley — the period in the 1970s defined by an ethos of purism, leaving as little hardware in the rock as possible, and learning to do the most adventurous and challenging routes without direct aid from equipment. She spent the requisite time living in the parking lot of Yosemite’s legendary Camp 4 and climbing the crags of Joshua Tree with now-famous climbers such as John Bachar and John Long — devoting the daylight hours to the wall and making lifelong friends at night.

Rock climbing was a fast love for Maria. She described it as “meeting the mission,” a formidable task that she could learn to conquer. It spoke to her desire to take the hard way, and find the solutions to difficult problems. And it was fun. In the Yosemite Valley of the 1970s, climbers reigned supreme. One year during huge spring floods, the National Park Service shut the park down, but several climbers managed to stay behind. In the mornings Maria and her friends would venture down to the water singing river songs. They swam through the freezing runoff and sunbathed on the bridges, which poked out of the water like islands.

“[She just had] dozens of friends and acquaintances she would be involved with every morning after breakfast. It was the big powwow with Maria at the center of it,” said Jonny Woodward — a formidable rock climber to whom Maria was married from 1986-2000. The two met at a climbing exchange in England, and then traveled around the U.S. together, living on the road and climbing, before becoming romantically involved. “Maria was just such a big part of that community, such a central character for so many people.”

A skilled climber who prided herself on technique rather than brute strength, she was also a natural mentor for the other women in the male-dominated climbing scene. She was the first woman to ascend Valhalla — a route at Suicide Rock that only a handful of other climbers in the world had completed at the time. Climbers who did the route were considered “Stonemasters,” an elite designation that meant you were one of the best. And she didn’t just climb Valhalla, she flashed it — that is, succeeded on her first try without falling. This was just one of several first female ascents she made around the state.

“Maria was the first person I ever saw climbing really hard,” climber Mari Gingery told writer Corey Buhay in 2017. “I rounded the corner, and there [she] was doing this route called Valhalla … Maria had her little shorts and sunglasses on, looking like she’s from Newport Beach, and all I could think was, ‘Holy crap. That’s how it’s done.’”

In 1984, Maria was living in Fullerton and working at Great Pacific Ironworks, the retail store for Chouinard Equipment — Yvon Chouinard’s climbing gear company that would eventually become Black Diamond. Soon she was hired into a customer service role by Peter Metcalf, co-founder and former longtime CEO of Black Diamond. By 1985 she had created a position for herself as Director of Marketing.

Maria was a firebrand and a groundbreaking business woman. After Chouinard Equipment declared bankruptcy in 1989, she bought the assets for the company along with Peter Metcalf and a handful of other former employees. Their team moved the headquarters from Ventura, California, to Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1991 and called it Black Diamond. A black diamond is a tough form of natural diamond that is formed from pieces of coal under pressure. The name was a perfect fit for Maria and her colleagues: a group of dirtbag climbers who believed they could transform a bankruptcy into a company that would make a difference for the outdoor community.

She worked as vice president of marketing and creative director for nine years, fighting hard to make sure the company was advancing along with the sport. She was committed to good ideas — when a friend or colleague introduced her to a worthwhile new concept or a superior piece of technology, she threw herself behind it.

“She saw the future of climbing out the windshield not the rearview mirror,” said Peter Metcalf. “She was always genius at being able to intuitively understand where the sport was and where it was going. … Nobody could do that better than Maria Cranor. She had an absolutely profound and integral influence on my life.”

Maria understood the heartbeat of climbing because she had lived it. Time after time, she shepherded progressive products through, working to convince others on her team to spend the extra money to invest in the future of the sport. She was in the background fighting for Black Diamond to introduce products such as the Spot bouldering pad and backpack, the ATC belay device and the Wiregate Carabiner — whose innovation quickly made them staples of their brand and the rock climbing world.

She traveled around the world going to trade shows, dazzling her competitors and then taking them out to drinks, where she persuaded them to spill their secrets. She would take what she learned and go back to Utah and make better, smarter products, all the while cultivating a sense of ethical competition and sportsmanship in the industry. Under her leadership, the Black Diamond catalog became the yearbook of the sport: If you wanted to know what was going on in the world of off-beat skiing or climbing, you would buy the catalog. She had an intuitive aesthetic sense, often traveling to LA’s garment district to study fabrics and trends to create color stories for the company’s products.

At the age of 50, Maria left Black Diamond and enrolled as an undergraduate at the University of Utah. True to her nature as a passionate and lifelong student, she took on a double major in physics and childhood development despite having already earned her bachelor’s from UC Berkeley some 23 years earlier. Her physics classes were particularly challenging because she had not taken math since high school and did not understand even basic algebra. But she was fascinated by the subject and determined to succeed. She received math tutoring from Black Diamond engineers and old friends, and thrived in the program.

After earning her bachelor’s of science from the university, she decided to go for a doctorate in physics there. She was admitted to the graduate program and studied under Richard Price, a leading specialist in general relativity who invited her to join his research group. She also became a lecturer, and her course on science writing would be the most popular in the department.

“I am a physics professor now, and I still recommend the things we read in her class to my students,” said Ryan Behunin — now a professor of Physics at Northern Arizona University — her student in her class who became a lifelong friend. “A lot of us have inflection points in our lives. And oftentimes, at that inflection point there’s a person who can change the trajectory of your life. [For me] she was absolutely one of them. I can say with 100% certainty that I would not be where I am now without having known her.”

In the days since her death, countless people have come forward to say the same: That Maria was standing at the crossroads of their lives with a twinkle in her eye and an insightful word of encouragement. Throughout her adult life in Salt Lake City, she and Jonny hosted famously fun dinner parties that would bring all kinds of people together. Renowned climbers and alpinists like Lynn Hill and Mark Twight would mingle with brilliant physicists and other friends of diverse backgrounds. She cooked homemade meals, sat everyone down at her table set with silver, and built bridges — deliberately seating people next to each other who she felt would get along. The parties fostered fascinating conversations, career development, and sometimes romance. They ended in the living room, where everyone would sit on the rug, drink coffee out of demitasse cups, and eat Haagen-Dazs ice cream out of the carton with a spoon.

“She really did improve people,” says Dale Goddard. “She created this context in which only their best selves could play.”

Maria did not ultimately finish her Ph.D., but that didn’t matter to her. She was more invested in learning than earning an advanced degree. As her life continued, she became very concerned about the future of the country and directed her formidable energy at causes she believed in. At the age of 67, she moved to Pueblo, Colorado, for seven months to work for the first Obama campaign, coordinating local activities and registering voters door to door.

Using money she earned in her Black Diamond days, she also became a philanthropic donor — often reminding family and friends that she believed the ability to accumulate substantive wealth is a policy flaw. Much of her philanthropy, both in terms of time and resources, was devoted to UC Berkeley, which she saw as a critical investment in the future of progressive thought and change in the state. She served four concurrent terms on the UC Berkeley Board of Trustees from 2013 to 2023, and sat on the College of Letters & Science Advisory Board from 2016 to 2020. Notably, she endowed a chair to the Museum of Paleontology, which she named after her father, Philip Sanford Boone. Additionally, she helped to establish the Glynn Isaac Postdoctoral Fellowships in Paleolithic Archaeology and the Desmond Clark Graduate Fellowship for graduate students in the Human Evolution Research Center.

“Maria stands up for what’s right, and I think people wanted to work with her because of that,” says Charles Marshall, the Philip Sandford Boone Chair in Paleontology at UC Berkeley. “They wanted her input, wanted to talk to her, wanted to be energized by her. Her impact was so much greater than her donations.”

Maria Boone Cranor is survived by her siblings, Eleanor Najjar, Sandy Boone, Graeme Boone, and Kitty Boone, as well as their children, Katie, Rebecca, and Helen; Alastair and Charlie; Annabella and Philip; and Alexandra (Mac) and Graeme. She is dearly missed by her chosen Salt Lake City family, April and Dale Goddard and their two sons–and her Godsons–Aidan and Julian. She is remembered and adored by the great many people for whom she was a source of encouragement, joy, inspiration, and friendship.

Alastair Boone is Maria Cranor’s niece. She is also the editor of Street Spirit newspaper in Berkeley.