Fred Ross Jr. was one of the nation’s leading organizers who began his work at an early age in the lettuce fields of California alongside Cesar Chavez.

But his work had an impact far beyond labor organizing on both a national and international level. In addition to a multitude of organizers who had an impact on electoral and other battles, he played a pivotal role in successful efforts to change U.S. policies backing oppressive governments in Central America, accelerating the naturalization of legal immigrants, and electing Nancy Pelosi to Congress for the first time.

Just weeks after celebrating his 75th birthday and receiving tributes from hundreds of friends and colleagues, he passed away on Nov. 20 of cancer at his home in Berkeley where he had lived for two decades.

One tribute came from former U.S. Labor Secretary and fellow Berkeley resident Robert Reich. “You have comforted the afflicted, and afflicted the comfortable,” he told Ross. “Your boldness and vision have been a source of inspiration to me and huge number of other people, working for social justice, labor unions, and the hopes and dreams so many people have for a better life.”

Dolores Huerta, a co-founder with Chavez of the United Farm Workers, said there were two words that come to mind when she thinks of Ross: “humble” and “noble.” “He was always so positive about everything,” said Huerta, now 92. “We had a lot of turmoil in the farmworker movement, but Fred always managed to stay above it. He remained a statesman.”

Ross’ brilliance was to take what he learned from UFW leaders like Chavez and Huerta, as well as his father, Fred Ross Sr., himself a legendary organizer, combine those lessons with field campaigns of local volunteers, and a savvy use of the media, and put pressure on employers, state governments and Congress to advance a variety of causes — and, when necessary, to help elect candidates sympathetic to those causes.

One of those candidates was Pelosi. He organized the Get Out the Vote campaign for her first successful run for Congress in 1987 in San Francisco. Ten years later he again joined forces with her as her district director in her Congressional office in San Francisco.

“I personally benefited from Fred’s organizational mastery: translating his policy goals into effective political action,” Pelosi said on hearing of Ross’ passing. “Without his early support and brilliant leadership organizing the ground operation of my first campaign, I would have never become a member of Congress.”

Throughout his career, Ross employed the house meeting, a hallmark grassroots tactic developed by his father while working with the Community Service Organization, a Latino civil rights group Ross Sr. co-founded in 1948. It involved setting up meetings with small groups of people in their homes to make change happen in their communities or in later years to organize unions.

His mother Frances Ross, an original “Rosie the Riveter,” was a shop steward in a World War II plant in Cleveland. She fought to help Jewish doctors immigrate from Nazi Germany.

“So fighting and organizing for racial and economic justice is in my DNA,” Ross said on many occasions. He acknowledged that he had gotten into a fair amount of trouble doing his organizing work — “good trouble, as John Lewis used to say.”

He recalled being knocked unconscious by a grape grower during a farm worker election, and being shot at by a security guard at a supermarket. “Luckily he was a bad shot,” he quipped.

By his own count, he had been arrested 39 times, “mostly for good causes.”

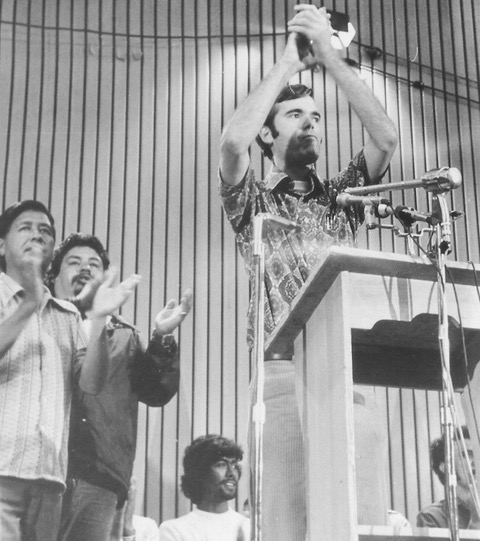

In early 1975, Fred conceived of and organized a 110-mile march against Gallo wines that began in Union Square in San Francisco and ended with at least 10,000 farm workers and supporters at the company’s headquarters in Modesto in California’s Central Valley.

One of the motives for the Gallo march was to put pressure on then-Gov. Jerry Brown to negotiate and push through the Agricultural Labor Relations Act, which was enacted in June 1975, and was the first law of its kind in the nation.

In the 1980s, Ross led Neighbor to Neighbor, an organization initially responding to the plight of refugees from Central America. It grew into a much larger effort to address conditions in those countries, and U.S. policies toward them, that contributed to the refugee problem in the first place. By putting pressure on individual congressmembers, and helping elect new ones, Neighbor to Neighbor contributed to ending U.S. support for the Contra rebel group in Nicaragua. Subsequently, Neighbor to Neighbor launched a boycott of Salvadoran coffee, one of that country’s most lucrative exports, which Ross argued helped underwrite the military regime there.

A key turning point was when longshore workers, led by labor leader Jimmy Herman, refused to cross picket lines set up by Neighbor to Neighbor and unload Salvadoran coffee cargoes up and down the West Coast, beginning at the Port of San Francisco. The threat of further economic damage played a part in forcing the Salvadoran government to reach an accord in 1992 with the FMLN, the leftist guerilla organization it had been fighting.

In 1998, Ross returned to his labor roots by organizing health care workers for the Service Employees International Union, working with Eileen Purcell, whom he described as “my organizing partner of a lifetime.” For 13 years with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 1245, he developed a nationally recognized program to train workers as “organizer stewards” who would participate in campaigns and electoral races around the country and then return to their regular jobs at PG&E and NV Energy in Nevada.

Most recently, Ross was working on producing a documentary film on his father intended to underscore the critical role of organizing, with an emphasis on one-on-one relationships that could be forged to build what he called “collective power.”

“As with his father, Fred Jr.’s labors were never about himself,” the UFW said in a tribute. “He was always about empowering others to believe they were responsible for the progress they won.”

He is survived by his wife, Margo Feinberg, a prominent labor attorney, and counsel to many significant labor organizing campaigns; their two children, Charley and Helen Ross; brother Robert Ross and sister Julia Ross; and a legion of loving friends and family members and generations of organizers.

In lieu of flowers, the Ross family asks that contributions go to the Fred Ross documentary project. Written condolences to the family may be sent to FredrossMemories@gmail.com.