In a district boardroom in May 1990, Martha Acevedo put forth a radical proposal: require all Berkeley High students to take an ethnic studies course. If it passed, the policy would be one of the first of its kind in the nation.

Acevedo, then a Berkeley Unified School District board director who had devoted her career to teaching ethnic studies, was nervous. But, she thought, if an ethnic studies requirement could pass anywhere, it would be in Berkeley, the first large school district to voluntarily desegregate its schools and establish an African American Studies department.

“I thought, if anywhere on the earth, the Republic of Berkeley should certainly have that class,” Acevedo told Berkeleyside in an interview 31 years later.

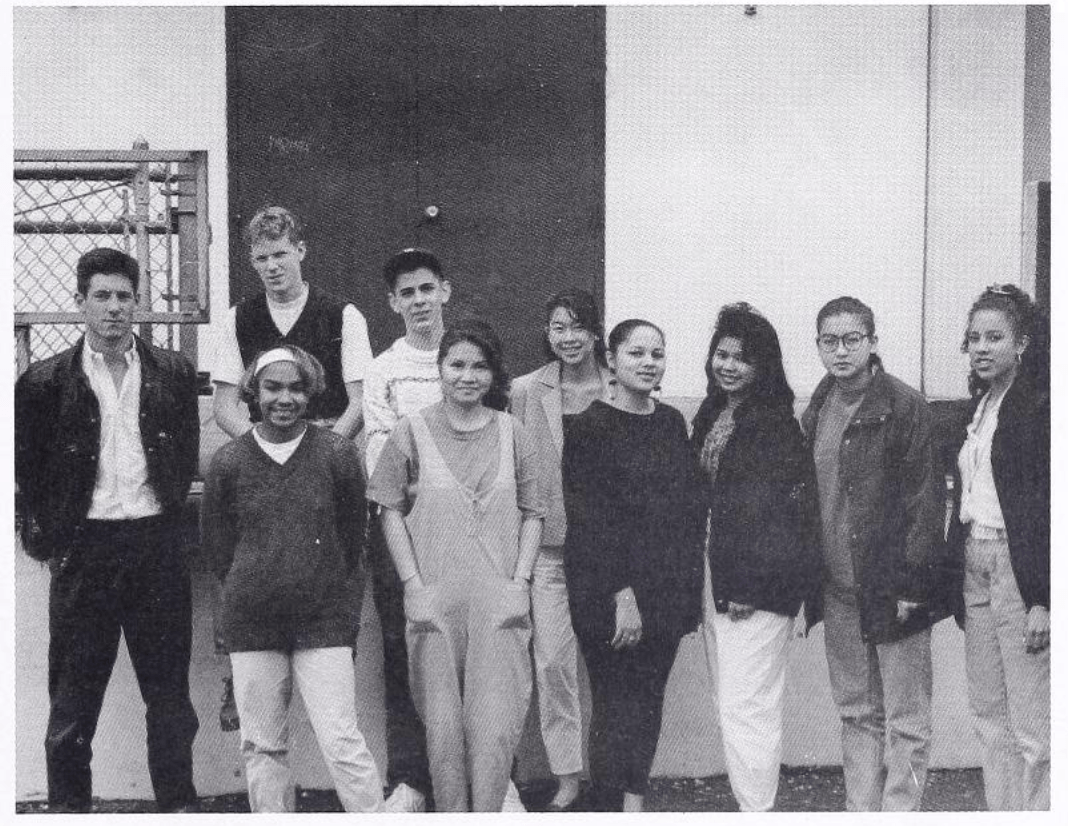

Three students from a new student group called Students Together Opposing Prejudice (STOP) joined her at the dais. The ethnic studies requirement had been the students’ idea, an effort to ease the racial tensions flaring among the student body at Berkeley’s large, diverse high school.

“We set out to influence our school’s education and curriculum,” Peter Coffin, a former Berkeley High student who joined STOP, wrote in an email this weekend. Like other students, Coffin was inspired by his politically engaged high school teachers. Some belonged to the East Bay chapter of the Black Panther Party, and they taught students a version of history not found in textbooks.

If, as Coffin put it, “intolerance was a product of ignorance and in some cases poor education,” then ethnic studies could be a viable solution, the students figured.

The students spoke passionately about the course, insisting that it be a requirement, not an elective. All students needed ethnic studies, they said. The Berkeley High principal, assistant principal, and chair of the history department spoke in support of the proposal, too.

Acevedo remembers that some board members were hesitant, but the political climate was such that they couldn’t speak out against it. “I don’t think anybody wanted to openly oppose it. I don’t think that they felt that they could,” she said.

The policy passed unanimously on June 13, 1990.

Berkeley’s requirement was ahead of its time. It would be over three decades before California became the first state in the nation to mandate a one-semester ethnic studies course for all high school students. Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 101 on Oct. 8, requiring students to begin taking the class by 2025.

“Berkeley’s never shied away from being the first in anything,” said Irene Hegarty, a former school board member who voted in favor of the ethnic studies requirement.

The idea of ethnic studies had its watershed moment in 1968 when a group of students at San Francisco State went on strike. One of their demands: establish a College of Ethnic Studies. Five months later, after student strikers brought police out in riot gear and the strike leader had been jailed, the university acquiesced, establishing the first College of Ethnic Studies in the country. The discipline wouldn’t start making its way into high school classrooms — even the most progressive ones — for another two decades.

Since then, not much has changed in the realm of ethnic studies in Berkeley: BUSD has maintained the semester-long required course and added upper-level electives in courses like Chicano Studies.

Now, on the heels of the new state requirement, Berkeley Unified is taking another step ahead, joining a handful of California school districts in developing a framework to infuse ethnic studies into every grade level, from transitional kindergarten through 12th grade.

Ethnic studies gets off to a rocky start

Berkeley’s ethnic studies requirement wasn’t particularly controversial at first, Hegarty recalled. Some parents grumbled that the extra requirement would mean their students couldn’t fill their schedules with more advanced courses — the course took the place of ninth grade study hall — but that was about it.

Students took pride that their advocacy had paid off: “Berkeley is well known for its politically conscious, let’s bring about change philosophy,” reads the BHS 1991 yearbook, which called the inception of the ethnic studies course “an accomplishment that took dedication and hard work.”

The district designed ethnic studies to be a “comparative analysis of the historical and contemporary experiences of the major racial groups” in both the U.S. and, especially, in Berkeley High — a course stressing “cross-cultural understanding and the breakdown of racial stereotypes.”

At the time, despite its famous legacy of integration, Berkeley High was socially segregated by race — rich white kids on the steps of the theater, Black kids on the slopes, a grassy section outside the main office, Latino kids near the staff parking lot. The tracking of high-achieving students into more advanced classes added to the racial segregation, according to Sean Smukler, who graduated from Berkeley High in 1991.

Smukler had joined STOP in the hope of improving the racial climate on campus, and helped push for ethnic studies for the same reason.

He said the group formed after a series of assemblies on African American history went awry, and he remembered fights that broke out between multiple students of different races. “There was violence,” Smukler said. “People certainly felt unsafe on campus.”

While the ethnic studies policy passed with little incident, the program got off to a rocky start in fall 1991, the first semester the class was taught.

Lacking teachers and curriculum, the school recruited anyone with a gap in their schedule, including physical education teachers and coaches, to ensure every ninth grader in a high school of 3,000 students could take the class.

Dana Moran was hired to teach ethnic studies with a handful of other teachers in fall 1993. By that time, the class had floundered without guidance for two years, she said.

“People had no idea what they were supposed to do,” Moran said. She heard horror stories: one teacher who let all the students of color leave because “only white kids needed the class”; another who made all the white kids apologize to the rest of the class.

Moran and the other ethnic studies teachers started meeting weekly to write the ethnic studies curriculum. The first iteration of the course divided the semester into three-week units on the history of marginalized groups: three weeks on African Americans, three weeks on Native Americans, three weeks on Jews, etc.

“It became increasingly clear that it was not possible to learn everything there is to learn about an entire group in three weeks. It just felt disingenuous and somewhat disrespectful,” said Moran, who still teaches ethnic studies at the high school. The design of the class eventually shifted to focus on concepts — identity, oppression — much like an introductory college course.

The stories that ‘need to be at the center’

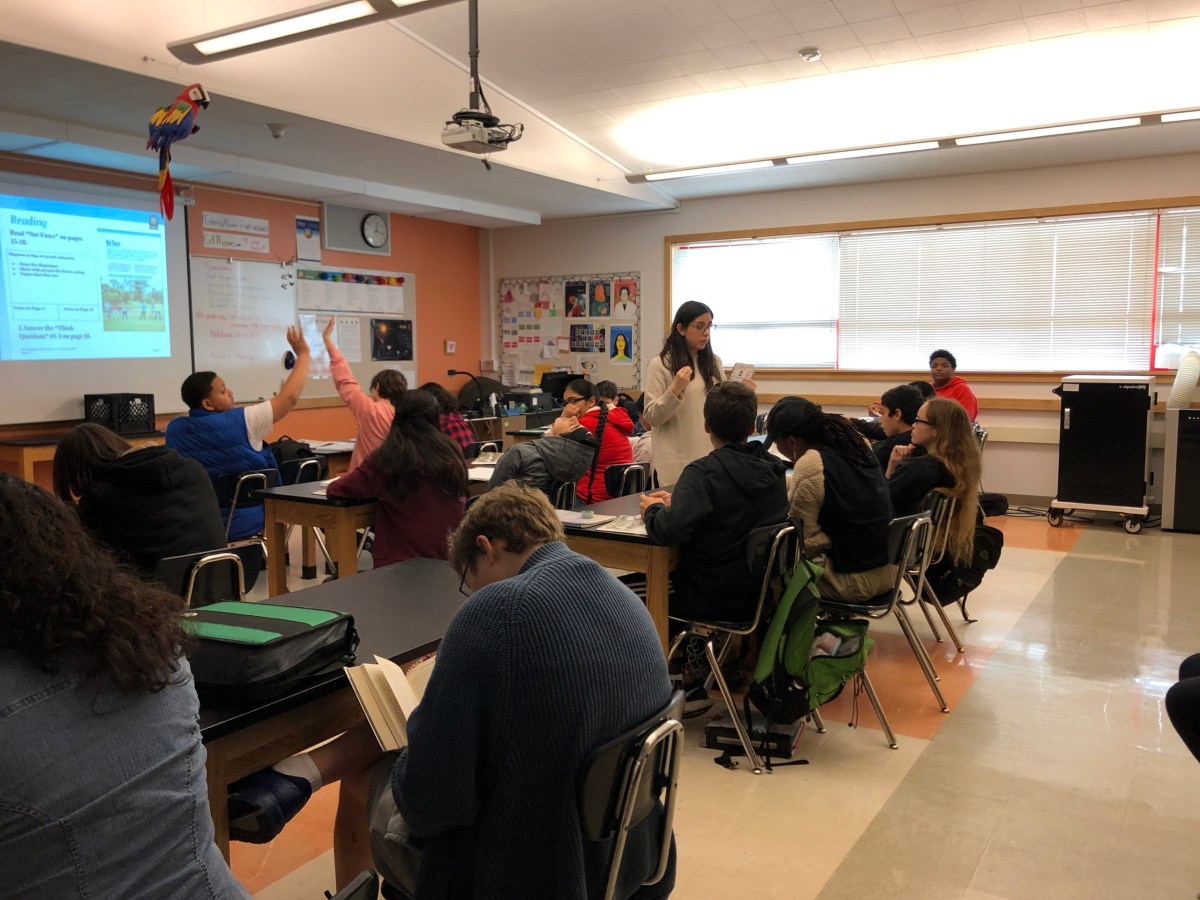

Today’s students taking ethnic studies grapple with big questions. Who am I? How do I live in a diverse society? What are the forces shaping people’s experiences? The topics span from race as a social construct to the three “I”s of oppression — internalized, interpersonal and institutional.

“Ethnic studies now is really about giving kids the ability to critically evaluate what is going on now and think about what they can do about it and what their part in it is,” Moran said. Moran said she hears from former students all the time who thank her for opening their eyes. One recently told Moran, half-seriously, that she taught her everything she knew.

The course’s aim isn’t so much to teach about instances of discrimination as it is to help students understand the systems of privilege and power that produce it, and the resistance required to overcome those systems, said Alex Day, another ethnic studies teacher.

“You see the veil drawn back a little bit.” — Alex Day, ethnic studies teacher

“As ethnic studies is starting to grow, starting to have some legs, we have to be really careful on defining what it is,” said KZ Zapata, an 11th and 12th grade English teacher. Zapata has been advocating for the expansion of ethnic studies for years. When she was a college student at UC Santa Barbara in 1989, Zapata went on a 12-day hunger strike to get an ethnic studies course established.

Zapata describes ethnic studies as an “unveiling” or “re-storying of history.” “Let us curate the stories that actually really need to be at the center,” Zapata said.

In one of his favorite lessons, Day teaches students how the concept of race was created by the Portuguese writer Gomes de Zurara, who justified the slave trade of Africans in 1453 by lumping African people — people of different languages, ethnicities, and cultures — together in opposition to the “superior” white man.

“You see the veil drawn back a little bit,” Day said.

That’s not to say that everyone agrees with the course content. Even in Berkeley, there are students who spend the semester arguing with Day that systemic racism does not exist.

“That’s fine. I mean, we can have that argument all year. They can get As thinking that,” Day said.

But Day said he’s never had a parent complain to him about the content of the course. In a country where school board members have received death threats from opponents of Critical Race Theory — a foundational component of ethnic studies, according to California’s model ethnic studies curriculum — Berkeley’s ethnic studies program has largely escaped such scrutiny.

Why wait until freshman year?

Berkeley High’s ethnic studies course covers a lot of ground — some say too much to do the material justice in just one semester. The topics encompass everything from culture and immigration to gender and sexuality.

“People think, ‘Oh, we’ve got ethnic studies covered.’ No, we don’t. We do not have ethnic studies covered, not in Berkeley High School nor in Berkeley Unified School District,” Zapata said. “The framework shouldn’t be one that just all of a sudden appears in ninth grade.”

Before students reach ninth grade, there’s no universal ethnic studies program. Individual teachers passionate about the subject have long incorporated it into their curriculum, especially in history and English. And at Longfellow Middle School, programs like Puente and Umoja offer culturally affirming education to students.

Now, 30 years after its inception at Berkeley High, BUSD is expanding ethnic studies beyond the high school.

That doesn’t necessarily mean every grade will have a distinct class on ethnic studies; the goal is to develop a framework ensuring students are exposed to the subject early and often.

In August, BUSD hired Joemy Ito-Gates, a long-time elementary school teacher in the district, to develop a five-year vision that weaves ethnic studies into each grade level and to provide teachers with guidance on how to begin incorporating it into their curriculum now.

“As a Multiracial Japanese American woman of color, I know what it is to be not just invisible in the classroom, but actively erased,” Ito-Gates wrote in an email. It wasn’t until college that she found her own life experiences validated and reflected in the classroom.

“As a district, we want our children to have affirming experiences every day, right now. We don’t want them to have to wait until freshman year at Berkeley High School or even later after they leave our schools,” she wrote.

For Ito-Gates, the fight for justice runs in the family. Her great-great-grandmother was abolitionist Lucretia Mott, who organized with Black women to end slavery and gain women the right to vote. Her grandfather investigated Nazis attempting to return as school teachers after World War II ended. Her mother played traditional Japanese instrumentals with musicians from other cultural backgrounds, such as jazz icon Pharoah Sanders, as a way to bridge cultural differences.

Her vision for ethnic studies is big and bold: “Ethnic Studies is what love in action looks like: love for racial justice, love for self, love for community, and love for the possibility of a world where everyone can belong as whole, joyful, free people.”

What the five-year vision will look like, though, is still in the beginning stages. Ito-Gates has developed an outline, but wants community input to drive the role that ethnic studies will play in the schools.

She has sent out surveys soliciting feedback from families and is holding listening sessions on the topic. She has also reached out to local Indigenous groups to explore the possibility of a partnership. For now, the hope is to recruit upper elementary school teachers to co-author and then pilot integrated units that infuse ethnic studies concepts into existing subjects.

The result, Ito-Gates hopes, will be a model for what K-12 ethnic studies should look like, in step with Berkeley’s progressive legacy.