Signs warning drone operators not to fly their robotic aircraft in the vicinity of the Campanile is a new element of annual efforts to protect UC Berkeley’s peregrine falcons as nesting time approaches.

This story was produced by UC Berkeley and first published on Berkeley News

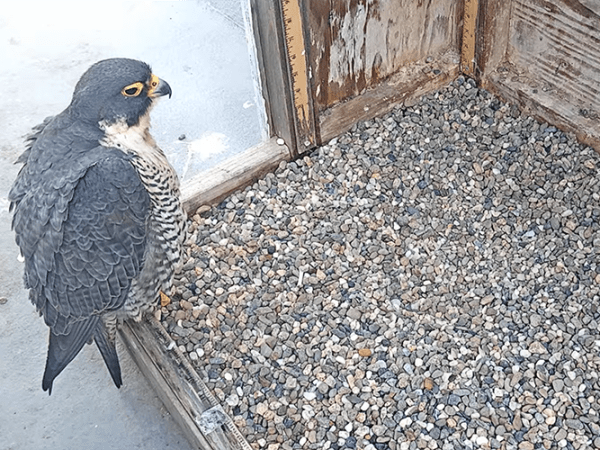

This will be the seventh breeding season for Annie, Berkeley’s longtime female falcon, who had a particularly close encounter last year with a drone when it approached the Campanile. She flew out and took a few passes at it, and then fortunately flew away. Dozens of known drone flights have occurred near the bell tower since Annie and her former mate, Grinnell, who was found dead in downtown Berkeley last March, arrived on campus in late 2016.

“Nobody wants to have to report Annie lost her wing or Annie lost her leg or Annie died because she was defending her territory from an illegally flying drone. Not me, not the public, not the campus,” said Mary Malec, a Cal Falcons raptor expert.

The bell tower ledge where Annie’s nest box sits is off limits from Feb. 1 to July 31, said Malec, unless reopening that upper part of the 307-foot-tall structure is necessary for human safety. An example, she said, was the year the light in the lantern atop the tower went out in the middle of nesting season.

Cal Falcons is posting four temporary yard signs, expected to be in place by Feb. 1, that include an image of a falcon flying toward a drone inside a “no symbol” — a red circle with a slash through it — and wording that includes a link to campus drone policy.

At all times, drones can only be flown on campus if operators meet UC Berkeley’s strict requirements. Those in the campus community who operate drones in a “reckless, unsafe or irresponsible manner” or in violation of federal law, the UC’s unmanned aircraft system policy or Berkeley’s campus policy will be subject to disciplinary action, according to Berkeley’s policy.

Non-university drones, the policy says, may be subject to UC Police Department enforcement, revocation of permission to fly over campus property and a ban on further flights over campus for up to five years.

Alden is absent, Annie and a new male are courting

Annie typically lays eggs in mid-March. This year, her mate Alden is “missing,” said Lynn Schofield, an ornithologist with Cal Falcons. “We cannot know where he is or if he will return. … It is not impossible that Alden, who we know tends to feed on shore birds, is away, following his preferred prey over the winter.

“He could return in the spring when the shorebirds return to the Bay Area and reestablish his position on the territory, although it’s more likely he’s moved on.”

A new male, who appeared at the Campanile at the end of November, “is definitely showing interest in the territory and has been bringing prey for Annie to signal his interest in her,” said Schofield. “He is working on the part where he delivers the food and then remembers to leave the prey for her to eat, but he’s getting better at it. He will probably continue to improve as the days get longer and he starts producing hormones that trigger more nesting behaviors.”

Schofield added that the recent rainstorms don’t typically affect adult falcons, which are “adept at hunting and navigating in inclement weather” and can go a few days between feedings.

But if the extreme weather continues into the breeding season, she said, “it could be a problem for egg-laying and incubation. If it is an extremely wet spring, Annie may delay egg-laying.”

Do your part to help protect campus wildlife

In the meantime, said Malec, drone operators need to be warned that flying unmanned aircraft systems without regard for campus rules could be deadly for Annie, other falcons that routinely fly near the Campanile, and eventually, young falcons learning to fly off the tower.

“Annie knows a drone is a danger and goes after it,” said Malec. “She knows it’s something coming into her territory that’s threatening to her.”

Even when members of Cal Falcons clean the falcons’ nest box and ledge or assist when the new chicks are banded each spring, “Annie perceives us as a threat,” she added, “and we’re not a danger.”

Educating drone operators is vital to protecting the campus’s resident wildlife.

“Just last Friday,” said Malec, “I saw a drone being launched directly west of the tower. I walked over and told them about the no-drone policy and the peregrines, and they very quickly brought it down.”

UC Police Department Capt. Sabrina Reich said she hopes the signage has an impact on unauthorized drone activity.

She added that community members should call UCPD to report violations “in a timely manner, so we may respond to investigate … and take appropriate action based on campus policy and law.”