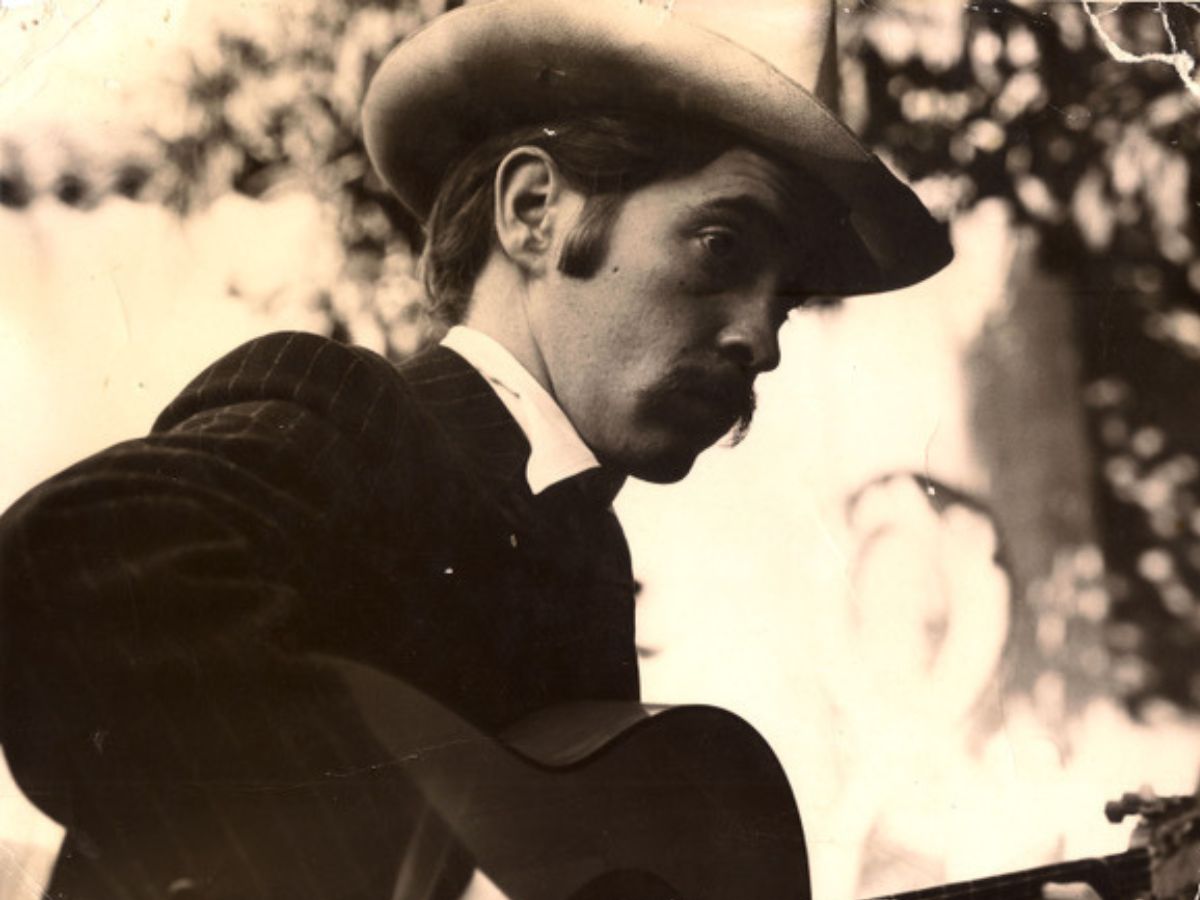

Flamenco guitarist David Serva Jones (1941-2022), an extraordinary musician and composer, a legend among American aficionados and highly respected among Spanish flamencos, died in the company of family at his sister’s home in Berkeley on Oct. 27, 2022.

“He was America’s greatest least known musician,” opined Paul Shalmy, a lifelong friend and former New York Herald Tribune journalist. He “focused his life, intelligence, energy and talent on a singular aim: the mastery of a musical form and tradition — flamenco — that in many ways, he loved more than himself.”

Born in Berkeley, to University of California professor Victor Jones and his wife, Annie Mae, who moved “north” from Birmingham, Alabama, in pursuit of a better future, Serva demonstrated a precocious musical talent on piano and other instruments, and first picked up the guitar at age 15, while a student at Berkeley High, learning from recordings and taking lessons in San Francisco’s Mission District. His musical career got underway while still in his teens, in a cave-like side room at the Spaghetti Factory in San Francisco’s North Beach (the center of Beat culture), as guitarist with Los Flamencos de la Bodega, the house troupe for impresario Richard Whalen’s long-running flamenco show, and later in New York City, notably in the West Village landmark Café Feenjon.

Traveling to Spain first in 1958 and again in 1962, thirsting for a deeper knowledge of traditional flamenco, he landed in the Andalusian pueblo of Morón de la Frontera where he first discovered a strong affinity for and became the disciple of legendary guitarist Diego del Gastor (1908-73). Diego’s particular Morón toque (playing style), became much the basis of David’s own. Throughout the 1960s, Serva returned to Spain numerous times, immersing himself further in Gitano (Spanish Roma) Andalusian culture and accompanying some of Spain’s most storied singers: Juan Talega, Miguel Funi, Manolito el de Maria, Luis Torres Joselero and La Fernanda de Utrera. Later, after the finish of a long-running gig as on-stage guitarist in the Broadway musical Man of La Mancha (greatly influencing composer Mitch Leigh), Serva moved to Spain permanently in 1971. Like many flamenco artists seeking their fortune in 1970s Madrid, his regional foundation developed further in some of Madrid’s most venerable flamenco tablaos (nightclubs), such as Torres Bermejas or El Corral de la Moreria. Serva understood that while Morón in the 1960s was an oasis of this aural and sung heritage that went back generations, a traditional flamenco now lost in the technical and often cluttered virtuosity of contemporary guitarists, to maintain a career in flamenco he would need to move beyond so localized and puristic a style.

Serva eschewed fancy modern pyrotechnics and played with an emotional directness and simplicity rooted in his encyclopedic knowledge of cante (flamenco song) and mastery of the art’s complex rhythms. Though he devoured material from every possible source, particularly blues, jazz (riffing on the likes of Miles Davis, Thelonius Monk, or Keith Jarrett), even Mexican rancheras, and experimented with unusual harmonies — the result was always very flamenco. His rhythm was perfect yet full of twists and turns. His music always had something to say. It left room to pause. It left room for silence. It gave voice to his unswerving engagement in this unique musical tradition and the marginalized world that nurtured it.

In the after-hours bars that were so much a part of the flamenco lifestyle, David walked the walk and talked the talk. He was known for his acerbic wit, but also for his impeccable, old-school manners, with a cultural intelligence and adaptability that allowed him to fit in as a foreigner in Spain generally, in Andalusia particularly, and among Gitanos especially. He was the only American to have carved a successful five-decade professional career as a flamenco guitarist in Spain in a time when Gitano (and non-Gitano) artists were often hostile and territorial about their musical heritage. Perhaps it was the depth of that immersion that attracted singers like flamenco’s fierce exponent Manuel Agujetas to knock at Serva’s door in Madrid early one morning in the 1970s, to summon him to a studio session as his accompanist, later playing on several of the cantaor’s acclaimed recordings (as well as state TV appearances). In 1990, he played in Seville’s Bienal de Flamenco both with Gitano guitarist Pedro Bacán’s “Nuestra Historia al Sur” and on the night dedicated to the Gitanos of Morón and Utrera, rather than the night dedicated to foreign artists.

Serva, who borrowed his stage name from the Caló (Spanish Roma dialect) word for “Seville,” spoke Spanish with an Andalusian accent so “down-home” that many flamencos had no idea he was not a Spaniard. In later years, younger Gitanos would address him as tío (uncle), a term reserved for elders of respect. While his passion lay with accompaniment, and he excelled at it — knowing just how to complement a singer or dancer — he did release a solo CD, Son Gitano en America, in 1995 — a near flawless recording of a live performance in Toronto’s St. Andrew’s Church, known for its acoustics.

His work, interspersed with festivals, tours, and artist-in-residence sojourns, took him from Madrid to Tel-Aviv, Mumbai, Tokyo and beyond but also, time and again, back to San Francisco. Highly influential in the Bay Area’s thriving flamenco scene, arguably the largest and most durable flamenco performance community outside Spain, he was a portal to, and ambassador for, traditional pueblo-style flamenco. As local flamenco guitarist Kenny Parker said, “David was one of the absolute pioneers, and I respect him because he did this over 50 years ago when it wasn’t easy, under Franco, when the bathrooms in Spain were dirty, and it wasn’t so attractive to tourists. He was the one who made the most inroads there and has influenced a whole bunch of people. … It’s a tremendous accomplishment.” Another student and friend commented, “He opened a crack in the door that so many of us were later able to step through, in ways that were utterly transformative … He also gave us a tantalizing and haunting glimpse of what it means to be free.”

As both aficionado and maestro, Serva earned the esteem and affection of his colleagues, as evidenced by the outpouring of appreciation and condolences from Spain and beyond. Charming, caring and generous to a fault with his cultural know-how, he nevertheless drove a hard bargain. His natural air of authority could be intimidating and his sardonic humor unwittingly cruel. As his lifelong friends, Berkeley-based screenwriters Janet and David Peoples said, “‘Jonesy’ was the king of cool, as well as master of the pithy comeback.”

Over the years, his single-minded pursuit of flamenco and its attendant lifestyle also took a toll on his family life, chronicled in the award-winning film Gypsy Davy, written and directed by his daughter, that premiered at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival.

David is survived by his sister Patricia Ungern nee Jones; his wife, Claire Chinoy (AKA Clara Mora); his children Martin David Jones (son of Mallory Pred), Rachel Leah Jones (daughter of Judith Jones nee Greenberg), Pablo Martin Jones Johnston (son of Cynthia Johnston), and Nandi Elaya Chinoy Jones (daughter of Claire Chinoy); and his grandchildren Michelle Isadora Margo Bellaiche and Martina Jones Morgade.

He left an indelible musical mark both in the U.S. and in Spain, was much loved, and will be sorely missed.